Future Proofing Representation in Measurement Means Jettisoning Legacy Mindsets and Methodologies

Or how I learned to love the fortitude of big data

The smarter way to stay on top of broadcasting and cable industry. Sign up below

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Recently, one of the old-school, panel-based currency providers has been suggesting that companies developing measurement solutions based on big data assets are somehow disadvantaged relative to panel companies in representing diverse audiences.

Not only is this untrue, but this sort of measurement fear mongering does the industry a disservice in the face of rapid tech advancements and consumer change. Progress isn’t owned by a single company and if the internet age has taught us anything is that innovation isn’t either. After all, it was the grandfather of modern computing Alan Turing who noted that “sometimes it is the people no one imagines anything of who do the things that no one can imagine.”

VideoAmp pioneered the integration of Smart TV ACR data and Set Top Box data into a single, commingled footprint. We use this footprint for measuring exposure to content and advertising across screens. This data has begun to be adopted by both buyers and sellers as currency data in the planning and buying of advertising.

In regards to both cultural and operational values (i.e. how we live, and how we measure), at VideoAmp we take Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) very seriously. DEI is threaded through the way we behave as a company. And it is threaded through the ways in which we endeavor to measure and report on media audiences. So it is incumbent upon me to address this unfortunate characterization.

Let me start off by noting that in my first job, at Arbitron in the 1980s, I spent seven years responsible for maintaining the TV meter panels as demographically representative and fresh. Later, at Comscore, I oversaw the panel team for about a decade. So even though I work at a company that makes use of Big Data, I know a thing or two about the care and feeding of panels to ensure there is no bias.

First off, anyone in the media research space who thinks panels are immune to issues with minority representation must have a short memory. It’s difficult to forget the controversy that led to Don’t Count Us Out. Then, a few years later, there was this. In that latter article, the money quote for me was that “the radio listening habits of over four million ethnic minorities are represented by only 500 Arbitron recruits.” Which has been, for the most part, the primary reason panels have fallen from favor as the primary method for counting audiences.

In both these cases, the CEOs of the companies in question ended up having to testify in congress.

The smarter way to stay on top of broadcasting and cable industry. Sign up below

Beyond congressional inquiries underpinned by delicate panels, let’s look at the facts in context with the current and future state of consumerism.

We know that diverse populations are differentially represented in the big data TV assets companies like VideoAmp use to count audiences to content and campaigns. Part of the reason we use multiple data sources, and that we combine both Smart TV data and Set Top Box data, is to minimize these variances. According to CIMM, in a paper titled “Combining Set Top Box and Smart TV data,” authored by Janus Strategy & Insights and pre-meditated media, 88.4% of the U.S. population has either a Smart TV, a Set Top Box, or both. Now, that missing 11.6% may seem troubling, until we compare it to the typical response rates of a metered panel; anyone who tells you with a straight face that these exceed 20% is being disingenuous. But hell, let’s call it 40%. So panels systematically miss covering 60% of the population in their small samples, compared to the 11.6% missing from Smart TV and Set Top Box data in our tens-of-millions footprint.

But what about diverse segments?

Historically, when audience measurement purveyors think about demographic representation, we express it in terms of proportionality. A perfectly proportional representation is 100 (meaning, the percent of the demographic characteristic in your panel, and the percent in the universe, is the same). A proportionality index of 80 for Hispanics indicates that for every 100 Hispanics you should have in your sample, panel or footprint, you have 80. An index of 120 would mean that for every 100 Hispanics you should have, you have 120. In both cases, best practices would indicate weighting such that, post-weighting, both the overages and shortfalls are corrected for.

In a deck presenting the above findings, CIMM found that among Set Top Box (labeled “Pay TV”) universe, the proportionality of African-Americans was 95; of Hispanics, 87. Among the universe of Smart TV households, the proportionality of African-Americans was 96; of Hispanics, 113.

In all the years I spent managing panel demographic composition, I would have been thrilled with these proportionality indices. Any demographer would.

Now to be clear, the fact that some portion of the population has neither Smart TV nor Set Top Box is a coverage issue we take seriously, and that we correct for using weighting. However, we know that this 11.6% may well use TV differently than the portion of the population we do cover. It is worth noting, though, that a significant portion of that 11.6% slice are broadband-only (BBO) households. We don’t project linear tuning to BBO households; rather, we cover them via direct census measurement of streaming. And of course direct census measurement may be said to be bias-free.

Now, let’s turn to issues of minority representation with panels.

We know that all survey response rates have been dropping for years, and that panel response rates are chronically low; we know too, from issues with Nielsen during COVID, that TV meter panels may require in-home visits to be maintained, and that without these visits, panel composition decays. So low response rates (i.e. low population representation), coupled with issues around panel maintenance, raise some important questions. What portion of the population that is initially selected to be in the provider’s panel, ultimately ends up IN the panel? What demographic biases exist between installed households and refusal households? Do different ethnicities attrite from panels at different rates? What is the ethnic diversity of the recruitment staff? Are panel companies sending African-Americans into African-American neighborhoods? Chinese speakers into Chinese neighborhoods? And how differently is the use of television among the majority of the population that is not represented in panels, as opposed to that portion who are? These are some of the questions clients should be asking their panel providers.

Ultimately, both panel providers and Big Data providers are prone to the same issue – reporting household composition systematically differs from the universe by demographic, and by other characteristics. And both types of data providers account for variances in representation versus census in the same way – by weighting. And, both types of data providers remain subject to the biases that cannot be fixed by weighting – that is, the extent to which that portion of the population not covered, deviates from that portion covered, with respect to the relevant behavior. Weighting corrects for the number of African-Americans, for example; but not for any potential difference between the African-Americans you have under measurement and those not represented.

But because the portion of the population – both at large, and by race and ethnicity – is far better represented in big data assets than in panel responders, the potential magnitude of this error is in fact far greater in panels. And this is important, so let me state it again. Big Data assets represent a larger portion of the population than that represented by that unique sub-stratum of people who end up in panels.

Truth Sets?

Finally, I’ve seen some posturing that panels are the ultimate truth set for how ethnic subgroups watch TV. This is false. Panels are not a solution or “truth set” to understand diverse audiences and technology. Audience measurement companies use census data and Universe Estimate studies to control both panels and Big Data assets (census for population, universe studies to understand how that population uses technology). At VideoAmp we use the CPS from the IU.S Census Bureau, which leverages surveys to update the decennial census in the years between fielding (most if not all companies in the measurement space use CPS). We also sponsored and have access to the Advertising Research Foundation’s DASH study, and we subscribe to the Kagan Media data, now under the auspices of S&P. Studies like these are then used as an input for correcting biases and shortfalls in both big data footprints AND panels. Panels are a beneficiary of universe “truth set” studies; not a source of them.

To Sum Up

This is not intended to be a slam on panels; VideoAmp currently works with two panel companies, TVision and HyphaMetrics. Rather, this is to correct the misperception – unfortunately disseminated by a panel provider – that somehow only a panel is immune to misrepresentation of diverse audiences. Frankly, having worked with both big data and panels, I would argue that the opposite is the case. Panels and samples have been fraught with issues around diverse representation since audience measurement has been around.

To attempt to build a system totally free from bias is a fool’s errand; rather, we should endeavor to build a system where the biases may be known, understood, quantified, and corrected for. At VideoAmp we strive to do this, and to constantly improve. One of the benefits of the Big Data assets we deploy is that their potential biases are more easily known – and thus, addressable. In fact, without Big Data, we would be blind to the ways that the millions of Americans not represented in panels are using media.

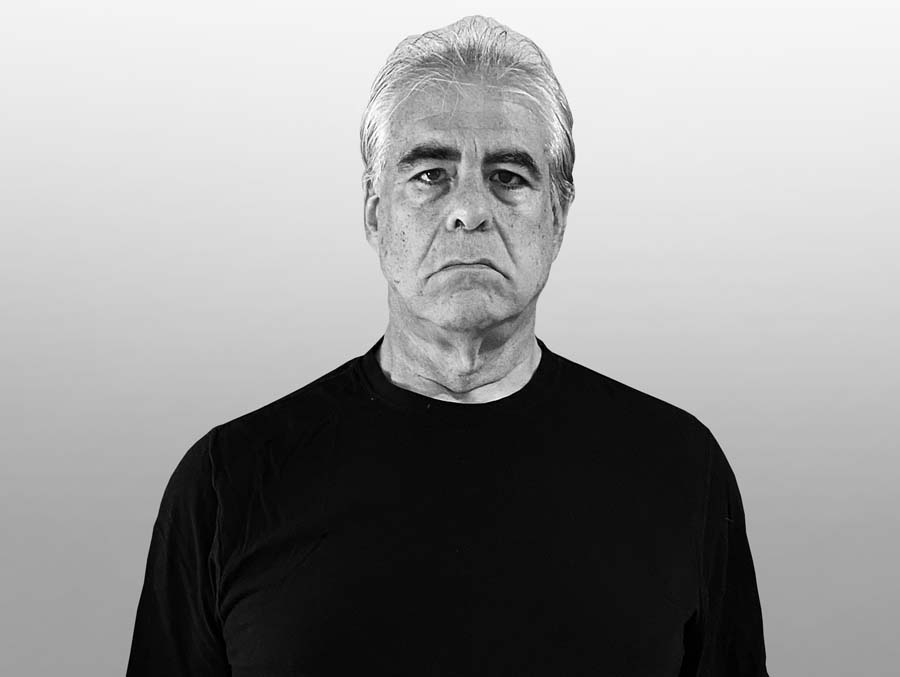

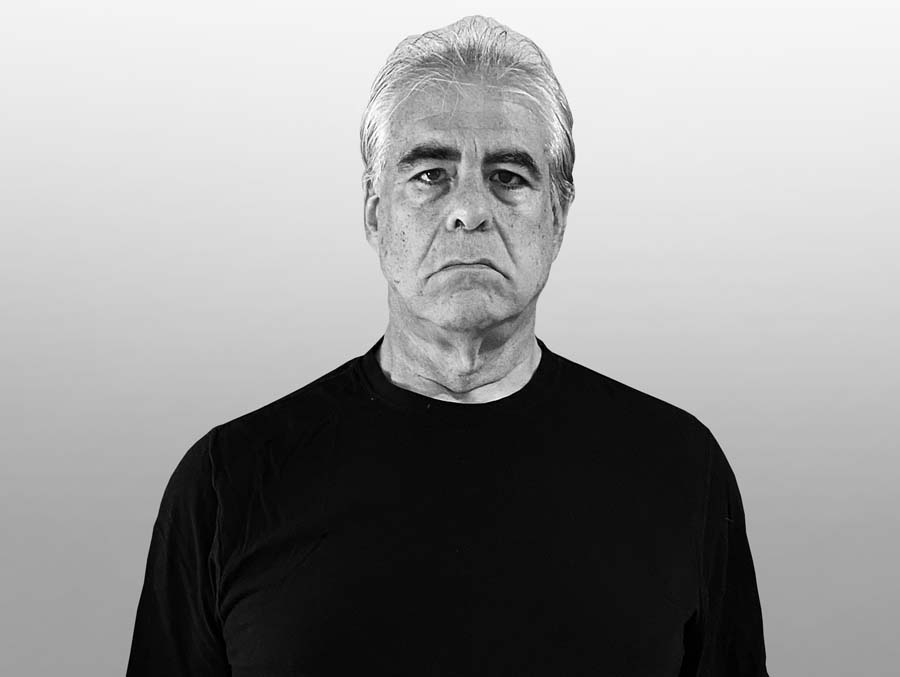

As VideoAmp's chief measurability officer, Josh Chasin boasts over 30 years of market research and audience measurement experience. He brings his expertise in audience measurement to the role with a focus on cross-screen measurability and its influence on advertising’s ever-evolving landscape. He is past president of the Media Research Council and was the recipient of the esteemed Erwin Ephron Award in 2020. When not focusing on advertising, Josh is a gold and platinum record holder with his liner notes for the Allman Brothers Band's 2004 DVD, “Live From the Beacon Theater,” earning him the honor with the Recording Industry Association of America.

Josh Chasin is the chief measurability officer at VideoAmp