B+C Hall of Fame 2022: ESPN

Sports programmer is first Iconic Network honoree

The smarter way to stay on top of broadcasting and cable industry. Sign up below

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In the year 2000, Espn Curiel was born in Corpus Christi, Texas, and Espen Blondeel was born in Michigan. At the time, Espen Blondeel’s father, Chad, told the Associated Press he watched SportsCenter at least three times a day.

Soon, there was a rash of kids named after the cable network, which goes to show how deeply fans were being touched, how legendary ESPN quickly became — and why it is the first Iconic Network to be inducted into the B+C Hall of Fame.

Such glory was not assured when founder Bill Rasmussen struggled to find financial backing for his crazy idea of a 24-hour cable network. When Getty Oil put up $10 million to get the Entertainment and Sports Programming Network off the ground in 1979, programmers filled its schedule with college basketball, slow-pitch softball, full-contact karate, America’s Cup sailing, boxing and a lineup of even more obscure sports.

Also: Welcome to the 30th Anniversary of the ‘B+C’ Hall of Fame

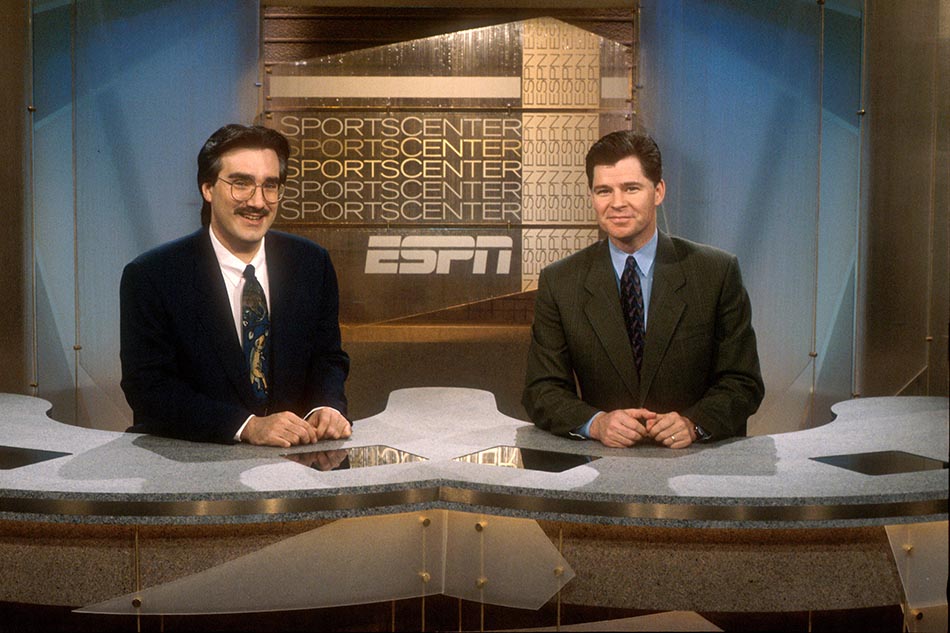

SportsCenter was one of ESPN’s original shows and a 24-year-old sportscaster with only a few months of television experience named Chris Berman was one of its first anchors. “Had they been two years old, they never would have hired me,” Berman recalled. “They couldn’t pick and choose.” Berman was already in Connecticut, where ESPN was headquartered, so the network didn’t have to pay his moving expenses, which made him an attractive candidate.

There were seven original SportsCenter anchors. “I called us the Mercury astronauts,” Berman said. “We went up in a rocket and we weren’t sure where the hell we were going to come down.”

TV’s Sports Section

Berman said one reason for ESPN’s early success was because it became a hometown sportscast for people who’d left their hometown, whether they’d moved or were just traveling. “If you’re from Chicago and you’re in a hotel in Seattle, it’s the same show,” he said. “We became your station.”

The smarter way to stay on top of broadcasting and cable industry. Sign up below

That was true of athletes as well. When ESPN was just starting, players would readily agree to be interviewed. Why? One told Berman he liked the channel but, more importantly, “ ‘My mom in Mississippi will have a chance to see this.’ I never thought of that and I’ll never forget that.”

George Bodenheimer, who would become president of ESPN in 1998, joined the network in 1981, 15 months after it went on the air. In his early days at the network, Bodenheimer played a key role in getting cable operators to pay a fee for the channel. They did that because of the strong support ESPN got from fans. Fan support was harder to gauge in those days, before the internet and social media. “We were using newspaper clips and the reactions we got on-site when we were producing events,” he said.

An early staple on ESPN was Australian Rules Football. Few Americans knew the sport, so ESPN put a graphic on its screen during a game that told viewers they could get a rule book by sending in a postcard. ESPN got thousands of postcards, Bodenheimer said. The network also would get calls from fraternities, firehouses and police stations asking where they could get ESPN so they could follow the NFL draft, he added. “People wanted hats. They stole our banners. These things anecdotally told us people liked what we’re doing.”

ESPN was a Little Engine That Could and 43 years later there’s a lot of us that still have that attitude. Viewers count on us to be there and deliver the sports news, the big plays. I hope that never changes. That’s a hell of a responsibility, but it’s a pleasure to deliver it.”

Chris Berman, ESPN anchor

One of those people was the late ABC World News Tonight anchor Peter Jennings, who called Bodenheimer one day to tell him everything had stopped in the newsroom because everyone was watching the National Spelling Bee on ESPN. Another was the late Sen. John McCain. Bodenheimer was in Washington to lobby legislators on telecommunications regulations, but McCain was a devotee of the sweet science. “We talked boxing for 50 minutes and spent 10 minutes on the issues of the day,” he said. “All the politicians had favorite teams from their states and wanted to know when they were coming up on our schedule. It was fascinating.”

NFL Milestone

ESPN hit the big time when NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle let ESPN buy a package of Sunday-night games in 1986, meaning viewers needed a subscription to watch (except in local markets where stations simulcast the games).

“That was obviously a game-changer,” Bodenheimer said. “Cable operators said they needed ‘punch-through programming’ and it didn’t get any bigger or better to deliver punch-through programming than when ESPN secured its first NFL contract.”

With the NFL on its roster, ESPN grew quickly. “We established a financial model that was going to work, and we began getting a fair fee from the cable operators and the business really took off,” Bodenhemier said.

ESPN was the country’s most distributed cable network by 1983 and its total number of subscribers topped out in 2011 at 100.1 million. According to S&P Global Market Intelligence’s Kagan, ESPN received $3.48 per month per sub from cable operators in 2007. That grew to $5 per sub by 2012, $6.91 per sub in 2017 and hit $8.81 a sub in 2022, by far the highest in the industry. Kagan said cash flow peaked in 2014 when ESPN brought in $3.5 billion for The Walt Disney Co., which had taken control of ESPN when it bought Capital Cities/ABC in 1996.

ESPN’s influence grew beyond sports. SportsCenter anchors became household names and their catchphrases resonated from arenas to schoolyards. Berman’s “back-back-back” call as a home run neared the wall became well known, as did the nicknames he gave players like Bert “Be Home” Blyleven, Lance “You Sunk My” Blankenship and Oddibe “Young Again” McDowell.

In 1998 The New York Times acknowledged SportsCenter catchphrases, such as Dan Patrick’s “He’s en fuego;” Kenny Mayne’s “Your puny ballparks are too small to contain my gargantuan blasts! Bring me the finest meats and cheese for all my teammates;” Keith Olbermann’s “He puts the biscuit in the basket;” Stuart Scott’s “He must be butta ’cause he’s on a roll;” and Rich Eisen’s “You want me on that wall. You need me on that wall.”

“SportsCenter went to a different level in the early ’90s,” said author James Andrew Miller. “You had an unbelievable cavalcade of terrific anchors. Dan Patrick, Keith Olbermann, Robin Roberts, Bob Ley, Charlie Steiner, Craig Kilborn, Stuart Scott, Rich Eisen. This was an all-star lineup and there wasn’t anything else like it. It became real appointment television for people.”

Miller said it took a while for the anchors, sitting in remote Bristol, Connecticut, to become aware of their popularity.

The Walt Disney Co.’s acquisition of ESPN worked out great for Disney, Miller noted. ESPN crushed what little competition cable channels from Fox or NBC offered and ESPN’s profits helped Disney buy Pixar, Marvel and Star Wars.

Miller’s 2011 book on ESPN, co-written by Tom Shales, was called Those Guys Have All the Fun: Inside the World of ESPN. Miller said if he were writing a sequel, it might be called Those Guys Don’t Have All the Fun.

In 2015, Disney chairman and CEO Bob Iger acknowledged that cord-cutting was eating into ESPN’s subscriber count. Disney’s stock plunged. The company went through a series of layoffs that stunned network veterans after its irrepressible success. The departures included many of its best-known faces. ESPN’s subscriber numbers would drop to 76 million at the end of 2021.

In 2018, Jimmy Pitaro was named president of ESPN. Growing up, ESPN was on all the time at home and when he was in charge of Yahoo! Sports, “I woke up every day trying to beat ESPN,” he said. When he was interviewed by Iger to become head of Disney’s interactive unit, “I conveyed to him at some point, I would love to end up over at ESPN,” Pitaro said. “Being a passionate sports fan, it was my dream.”

But cord-cutting had reached nightmare proportions at ESPN when Pitaro took over. “By the way, that is still a challenge today,” he noted. The company was also preparing to launch ESPN Plus, its streaming direct-to-consumer business, which would grow to have 21.3 million subscribers by the end of 2021.

Sports Mission Continues

Pitaro said ESPN’s mission to serve sports fans anywhere, anytime hasn’t changed. “It is just as relevant, if not more relevant today than it ever was.” ESPN’s current strategy is to follow consumers, particularly young ones, which has meant being on Snapchat, TikTok, Instagram, Twitter, video games as well as streaming. That connects with the brand and gets them watching SportsCenter and other ESPN properties.

If you look at all the assets that we have and what we bring to the table in terms of our brand, our credibility, our trust, our reach, our production capabilities and the synergy opportunities with The Walt Disney Co., I feel like we’re in a really good place. I like our hand.”

— Jimmy Pitaro, ESPN president

ESPN research found that viewers expect a direct-to-consumer platform to give them access to live events plus shoulder programming and original films like ESPN’s 30 for 30 franchise. ESPN Plus has what Pitaro called infinite real estate and the technology to help fans find what they want to watch.

“The beautiful thing about ESPN Plus is you can put everything up and through personalization you can serve what you think is going to resonate based on a user’s consumption patterns,” Pitaro said. “The future is going to bring a more personalized, more interactive experience starting with the game. You’re going to have many choices. You’ll be able to watch a betting-themed broadcast, or a broadcast with different camera angles, or a broadcast that is a little bit lighter, more fun and entertaining like the Manning brothers [alternate NFL broadcast] currently on ESPN2.”

But Miller said ESPN still has to figure out how to manage in a streaming world where nonviewers don’t have to pony up through their cable operators whether or not they watch the channel. There’s also ongoing talk about ESPN being spun off from Disney. “I know it’s a big topic of conversation in Burbank and Bristol,” Miller said.

Whether or not that happens, ESPN will remain iconic. “Those four initials are a brand that is recognized around the world,” Miller said. ■

Jon has been business editor of Broadcasting+Cable since 2010. He focuses on revenue-generating activities, including advertising and distribution, as well as executive intrigue and merger and acquisition activity. Just about any story is fair game, if a dollar sign can make its way into the article. Before B+C, Jon covered the industry for TVWeek, Cable World, Electronic Media, Advertising Age and The New York Post. A native New Yorker, Jon is hiding in plain sight in the suburbs of Chicago.