Cover Story: SPACs: The New Final Frontier

Special purpose acquisition companies are all the rage for companies seeking quick funding, and content owners are beginning to take notice

The smarter way to stay on top of the multichannel video marketplace. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Media companies looking to raise money over the past several years had a few options: banks, private equity or going public. The latter, often the most lucrative, also came with the headaches of road shows, high fees from underwriters and the risk that their stock could be priced well below its owners’ idea of value. In the past year, though, media companies have begun to look toward an old financing vehicle, special purpose acquisition companies [SPACs], which offer a faster path to the public markets and, more importantly, the cash they need.

SPACs came on the scene in the 1990s and were thought of as a last resort for companies that couldn’t raise money any other way. With more than 100 SPACs created so far in 2020, raising nearly $44 billion, they’re becoming a preferred way to raise money quickly.

In the content space, the most prominent SPAC target is CuriosityStream, the documentary streaming service started by Discovery Inc. founder John Hendricks. CuriosityStream agreed in August to a deal with SPAC Software Acquisition Group (SAG), giving the programmer an enterprise value of about $331 million and an equity value of $512 million.

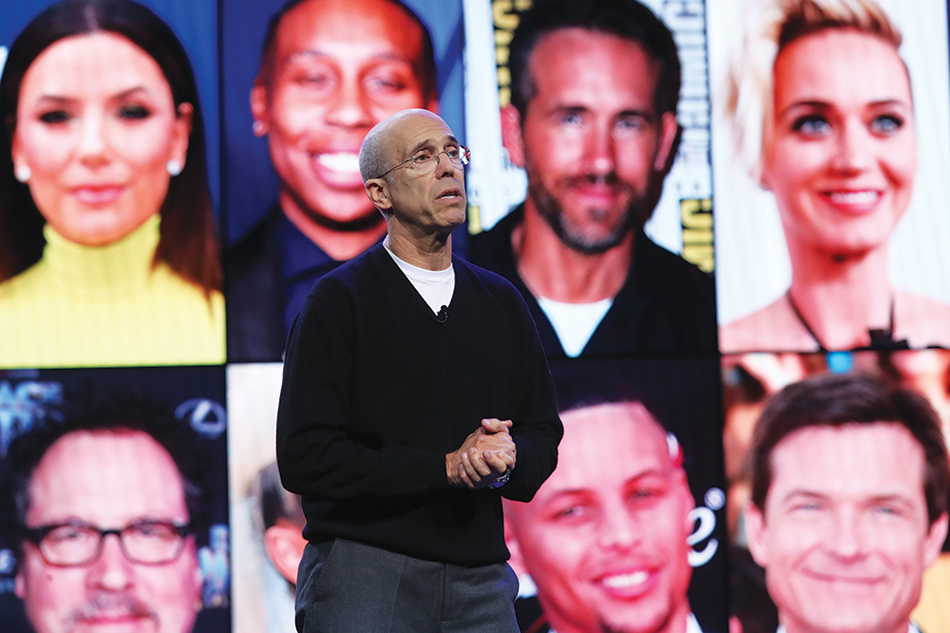

Other content companies are taking a look at the financing vehicle. DAZN, the streaming sports service headed by former ESPN chief John Skipper, said in August it would try to raise $1 billion, partly through a SPAC. Quibi, headed by former DreamWorks Animation chief Jeffrey Katzenberg, also has been said to be investigating its strategic options, including possibly going public through a SPAC. Last year, The Wall Street Journal reported that movie studio Lionsgate Entertainment was looking at potentially spinning off Starz to a SPAC, although no deal has been made yet.

What’s a SPAC Anyway?

On the surface, SPACs appear to be a no-brainer for investors. Essentially, a SPAC assembles a management team and sells stock — usually at about $10 per share — to raise money for future acquisitions. Once the money is raised, about 10% goes to the underwriter and the remaining amount is put in escrow. Once an acquisition is made — for at least 80% of the money raised — SPAC management receives 20% of the profits and investors get ownership in the acquired company.

Investors are betting that a strong management team will not only find a compelling property, but will manage it well and grow the stock price. SPAC management has a fixed time frame to seal a deal, usually 18 to 24 months, or it must return the money raised to investors. So, as long as an investor gets in early — and doesn’t pay more than the initial public offering price for the stock — they recoup all or most of their investment.

The smarter way to stay on top of the multichannel video marketplace. Sign up below.

For the companies that are acquired, SPACs are an attractive way to go public without having to go through the hassles of an IPO. Often they can raise more money than they would through a traditional IPO, although companies that raise money through SPACs could be considered to be riskier.

So why are SPACs suddenly becoming so popular? According to those who have formed them, it’s a combination of simplicity — there is no need for the face-to-face road shows required in an IPO, a big plus in the COVID-19 era — and more accurate valuations.

Curious About SPACs

CuriosityStream’s decision to essentially be acquired by a SPAC was a bit of a surprise in August, but president and CEO Clint Stinchcomb said the company carefully evaluated its options when looking to take the next step. “What we liked about it compared to an IPO, it’s a faster process,” Stinchcomb said, adding that while there is due diligence, it’s less stringent than an IPO and puts less strain on the management team. “Next is more certainty around pricing as you go to market than there is with an IPO.

“Another big component is with a SPAC, you can use forward-looking documents,” Stinchcomb added. “For a company like ours that is high-growth, early-stage, it’s helpful to share with investors what the future looks like.”

Companies looking to go the SPAC route have to do their homework, too, Stinchcomb said. “You have to sift through how big they are, how much money they raised, what they think they can bring to the deal,” he said. “In working with SAG, they had $150 million, which we thought was the right size for us. It enabled us to pump a lot into programming and marketing and get to cash-flow positivity in the not-too-distant future.”

The deal appealed to the company on a personal level as well, Stinchcomb added. SAG chairman Jonathan Huberman has a strong background in technology, and as former CEO of Ooyala, a video workflow company that has worked with several streaming companies, Huberman was familiar with CuriosityStream and its business.

“He knew of us, we knew of him, we had people in common that we knew, both professionally and secondarily and even personally,” Stinchcomb said. “We talked to a lot of SPACs and we really liked Jon and his partner, Mike Nikzad, and their shared vision for what we all thought was possible for CuriosityStream.”

The proceeds from the SAG deal will be mostly used for programming and marketing. CuriosityStream has said it wants to grow its content library from about 3,000 tiles to 12,000 in the next five-plus years.

The transaction also creates a deal currency in the SAG stock — which will trade on the NASDAQ under the symbol “CURI” after the deal closes, expected in Q4 — for both future M&A and to give early CuriosityStream investors a way to monetize their stakes.

“The influx of capital provides us with the opportunity to be flexible as it relates to M&A, and we will be,” Stinchcomb added. “We’re heavily focused on building the business organically and we’re quite confident in considerable organic growth. We’re monetizing content right now across five business lines, streaming at our core. Obviously, we have a growing and robust bundled distribution business with cable, direct-to-home and wireless providers around the world, we have a corporate association partnership business, an advertising and sponsorship business and we have a program-sales business.

“We’ll grow aggressively organically,” Stinchcomb added. “Where there are inorganic opportunities we’ll take advantage of those as well.”

But There’s a Risk

While they represent a quicker way to raise cash for companies, SPACs are not risk-free. Although the odds for a SPAC finding a target company have risen over the years — last year about 89% of SPACs found a company to invest in — the shares can fluctuate wildly even after a deal is made. And sometimes making a deal isn’t enough.

For example, in 2016, media investor Haim Saban raised about $200 million through a SPAC, Saban Capital Acquisition, and agreed to merge with camera maker Panavision and Canadian production house Sim International in September 2018 in a deal valued at $622 million. But they scrapped the deal in February 2019 because of delays caused by a government shutdown and a volatile stock market. Saban Capital Acquisition was shut down soon thereafter.

Others have launched successful SPACs. Eagle Investment Partners has launched six since 2011, raising $3 billion for targets as diverse as an Indian satellite-TV company to sports-betting behemoth DraftKings. Black Entertainment Television founder Robert Johnson raised about $125 million through RLJ Acquisitions in 2011, merging with Image Entertainment and Acorn Media Group, forming RLJ Entertainment a year later. RLJ Entertainment was sold to AMC Networks in 2018.

In August, Trine Acquisition, a SPAC created by cable legend Leo J. Hindery Jr. in 2019, agreed to purchase 3D printer technology company Desktop Metal in a deal that values the company at $2.5 billion. Trine had raised about $260 million through its IPO.

But those can be the exception. According to Renaissance Capital, since 2015, only 89 of the 223 SPAC IPOs completed mergers and had taken a company public. During that period, SPAC shares have lost an average of 18.8% and had a median return of -36.1%, compared to the average aftermarket return of 37.2% for traditional IPOs since 2015.

The numbers appear to have gotten better in the past two years, especially after a company finds a target. According to SPACInsider, the average return on investment for SPACs that announced an acquisition between 2018 and 2020 was 47.6%.

According to SPAC Analytics, about 136 SPACs are currently looking for deals, with gross proceeds of $47 billion, and 228 have completed an acquisition, with gross proceeds of about $40 billion.

On Sept. 24 Securities and Exchange Commission chairman Jay Clayton told CNBC the agency will take a closer look at SPACs. “In some ways, it's very healthy; it actually creates competition around the way we distribute shares widely to the public market,” Clayton said. “And competition to the IPO process is probably a good thing. But for good competition and good decision-making, you need good information,” he said, adding that the agency would particularly focus on “incentives and compensation to SPAC sponsors.”

Clayton’s comments came weeks after electric truck maker Nikola, which went public through a SPAC deal earlier this year, fell under scrutiny after allegations that it has misled investors.

Behind Every Dark Cloud …

Despite that added scrutiny — and it should be noted that none of the companies currently involved in SPAC media deals are accused of wrongdoing — SPACs continue to flourish, and for some, could be the vehicle of choice for content companies seeking funding.

Accurate valuations are a key component of the popularity of SPACs, said former MGM chairman Harry Sloan, who with ex-CBS Entertainment chief Jeff Sagansky has launched six through Eagle Investment Partners. Sloan and Sagansky’s latest SPAC — Flying Eagle Acquisitions — purchased mobile gaming company Skillz in September in a deal that values the company at $3.5 billion. In 2019, its Double Eagle Acquisitions SPAC raised $425 million, purchasing sports gaming giant DraftKings and SBTech in a deal that valued both companies at $3.3 billion.

Sloan doesn’t believe that SPACs are better than IPOs, but in certain situations they make a lot of sense. “If you have a company with no comps that’s a new business and you don't know how to value it, the SPAC process gives you an opportunity to have several meetings with the investors,” Sloan said. “They figure out what the valuation should be and they can figure out whether they want to be involved.”

Do they ever want to be involved: According to Eagle Investments, when Diamond

Eagle Acquisitions finished its merger with DraftKings, it had 27,000 retail investors.

Not for Everyone

SPACs haven’t always enjoyed the greatest of reputations. In the past, SPACs, also known as “blank check” companies, had a reputation for not doing deals, and only making money for the people who formed them, not investors. Companies targeted by SPACs were often dismissed as operations that couldn’t muster funding in any other way.

But changes in the structure over the past few years — primarily the requirement that the money raised be held in escrow, where it can gain interest while the principals look for acquisition targets — has changed the way people look at SPACs. In addition, SPACs began attracting more executives with actual experience in the industries they targeted.

At the same time, name-brand investment banks began investing in SPACs, like UBS, Barclays, Credit Suisse and others, with some even starting their own. In the past, SPAC investors were mainly boutique bankers.

Around the same time, the quality of the companies that merged with SPACs began to improve as well. Virgin Galactic, billionaire Richard Branson’s space-tourism venture, merged with a SPAC in 2019, raising about $800 million. Hedge-fund legend Bill Ackman put his imprimatur on the structure in July, launching Pershing Square Tontine and raising $4 billion, the most ever for a SPAC, which helped further spur interest.

In August, Oakland A’s VP of baseball operations Billy Beane (of Moneyball

fame) teamed up with former Goldman Sachs investment banker and YES Network architect Gerry Cardinale. They raised $575 million in a

SPAC called RedBall Acquisition and are reportedly looking to purchase an English Premier League soccer team.

“These were never SPAC targets in the past,” said Gavin Cuneo, who with his father, corporate turnaround specialist Peter Cuneo, formed CIIG Merger Corp., a SPAC that raised about $260 million in December. “We’re able to consider all different types of opportunities here, and it’s also an attractive solution for targets now, whereas in the past it was looked upon as a second-tier option for them. Now, there’s plenty of tremendous companies out there looking for SPAC partners, so the opportunity of the deal set and the quality of the companies is very high.”

The quality level of executives running the SPACs is also improving. In addition to Sloan and Sagansky, who have well-respected track records in the media business, the Cuneos have equally strong reputations. Gavin Cuneo is a former investment banker and was chief operating officer and chief financial officer of Valiant Entertainment, which was sold to DMG Entertainment in 2018. Peter Cuneo has a long reputation for righting troubled companies throughout his career, including divisions of Black & Decker, Clairol and Remington Products. But he is best known for his work with Marvel Entertainment.

Peter Cuneo became CEO of Marvel in 1999, just after the comic book icon had emerged from bankruptcy and when, according to reports at the time, the company had about $3 million in the bank and could barely make payroll. After implementing a three-year turnaround plan in which the company switched its focus to licensing its characters for movies, television, video games and consumer products, Marvel got back on its feet and in 2005, launched its own movie studio. In 2009, when Cuneo was vice chairman, Marvel Entertainment was sold to The Walt Disney Co. in 2009 for $4.5 billion.

He said forming CIIG with his son in late 2019 seemed like a logical next step. “This started for me three to four years ago, when I looked back at the success we had at Marvel and the strategies that I put in place as CEO,” Peter Cuneo said. “I was very surprised at looking around in the industry, media and entertainment, and other than Disney nobody has picked up on those strategies. I thought this would be a great opportunity to get into this again and use a lot of those strategies that we used back then.”

CIIG still has about 16 months left to find a target and, according to Peter Cuneo, is looking at dozens of companies throughout the Technology, Media and Telecom space. “The entertainment-at home-businesses are particularly attractive right now, location-based entertainment is not,” Peter Cuneo said.

And as the media business moves toward a streaming model, that also presents opportunities for investors, Gavin Cuneo said. “Streaming — we love that theme, it’s one thing we consider in all the deals we are looking at,” he said. “It’s a major trend in the industry. The demand for content is higher than it's ever been and there are more and more streaming players.”

Gavin Cuneo used CuriosityStream as an example, adding that he and his father have known John Hendricks for years and that its deal with Software Acquisition Group is “emblematic of the demand for streaming content today and the attractiveness of it as an investment opportunity.”

“Everything we’re looking at in the media space, we’re looking to capitalize on this astronomical demand for content,” Cuneo continued. That includes the video space, music (which he said is ripe for a SPAC deal), gaming and sports.

Although many SPACs say they are looking for targets in the technology, media and telecom sectors, actual media deals are hard to find. Outside of CuriosityStream, recent SPAC media deals have been in the sports and gaming industries. While speculation was high that Lionsgate was looking at SPACs to spin off Starz last year — which hasn’t materialized — finding appropriate merger targets within the content arena is for some SPACs, like searching for the proverbial needle in a haystack.

“Almost all the SPACs are listed as TMT [Technology, Media and Telecom]. Content is something that most of them don’t want,” said FBN Securities media analyst Robert Routh, adding that while investors are interested in broadband distribution assets, available deals are scarce.

“What is out there that isn’t already owned by the big guys — AT&T, Verizon, Comcast, Charter or Altice?” Routh said. “What else is there that you could do that is going to make a difference so you can compete against any of those? The answer is not much and very little of that.”

One SPAC executive who asked not to be named agreed that finding media companies to invest in is hard because of the intense consolidation over the past decade. That consolidation wiped out many of the entrepreneurial companies that are often targets of SPAC investors. “Clearly, TMT is the answer,” said the SPAC executive that asked not to be named. “But you’re going to find more tech than ‘M,’ and more ‘M' than ‘T.’”

Adding to the problem is that traditional media doesn’t seem to fit the mold for current SPAC investors. “When you say there have been no media deals, partially that’s because when there are 20 SPACs, there are 20 people to do a deal,” said Enrique Abeyta, a former investment banker, hedge-fund manager and media and SPAC investor who is launching a SPAC-focused newsletter at Empire Financial Research. “I don’t know if we’re going to get to 200, but we very well might. The market is just a lot bigger. The other element is I think the SPAC investors in this latest generation are very focused on growth investments. And as a lifelong media investor, there’s not been a lot of growth in media.”

Rolling Up Content

Still, with that much money eager to find a home, SPACs could find their way deeper into the media space through more creative means, Routh said. One way would be to roll up content libraries from various studios, production houses or even specific rights for certain content.

Those rights, especially remake rights, are where the real value lies, according to Aquarius Content CEO Gary Pearl. Pearl bought the remake rights to Venezuelan telenovela Juana la Virgen in 2014 and remade it in America as Jane the Virgin, which ran for six seasons on The CW. Pearl said there is a lot of hidden value in libraries of dead studio labels that could be brought back to life with the right management and an ample cash infusion.

“I’ve been saying for the last two years that all of this old content is going to be worth more, not less,” Pearl said. “The convention says it’s worth less, and a lot of really smart people are invested in saying it’s worth less. Then, all of a sudden you see Friends and The Office sell for close to half a billion dollars.”

But why would a studio even consider selling its library when in the current streaming environment, libraries are only growing in value? Access to capital, according to one former programming executive. “It's hard to raise funds right now,” said Denise Denson, former Viacom programming chief and current chief operating officer of Molten, a tech firm that specializes in helping content owners track digital rights. “So people are looking at creative ways. And if it’s making some Sophie’s Choices and giving up some IP, they would probably do it in this market.”

Denson said she has already fielded calls from venture-capital firms looking for introductions to programmers to see what IP they had laying on the shelf, collecting dust. “I didn’t end up doing the intro, but I understood the idea,” Denson said. “They were trying to scrape up any major IP that people were, in this market, willing to let go, probably inexpensively. It’s really buy low and ultimately sell high. These are opportunistic moments.”

By selling remake rights, content creators could be sacrificing the future for short-term gains. But some producers, especially smaller houses, might not have a choice. “I don't think content owners have the leverage right now,” Denson said. “There is a lot of content and it’s a soft market and people are in need. If you're in need, that doesn’t put you in the best position.”

Sometimes, selling remake rights to one show can end up boosting the value of the rest of the library. “You can add value by recreating,” Pearl said. “When it comes to content, some people know that and some don’t. … My show, Jane the Virgin, was actually a Venezuelan title. At the time it was worth $50 million from the library. Because we remade that one show, the library went up to $250 million, 5 times. I don’t participate in that."

A SPAC also could be beneficial to programmers because they may see value in a content creator that others don’t. Though some have criticized the structure as paying too much for some companies in order to satisfy SPAC conditions, a content-focused entity could better exploit those assets.

Pearl remembered The Walt Disney Co.’s purchase of 20th Century Fox programming assets in 2018 for $72.3 billion — won after a hard battle with Comcast — and the entertainment giant’s 2006 buy of Pixar ($7.4 billion) and Marvel ($4.5 billion).

“They overpaid, in people’s opinions, for things like Marvel and Pixar. But did they?” Pearl asked. “They had a different use for it that other people didn’t have.”

According to Abeyta, most traditional media deals are more value investments, which SPACs are showing little interest in. But that could evolve, especially as more SPACs get created, because their structure allows companies to do more complex deals than through an IPO. As an example, he said a SPAC could technically roll up libraries from several different studios.

“There’s no way you could IPO that,” Abeyta said. “A SPAC sponsor could say, ‘We love this business plan, let’s do it.’ It’s just really pretty far afield from the mindset of where SPAC sponsors are now.”

Timing also is an issue, Abeyta said, adding that SPAC sponsors have about two years or less to get a deal done. Tying themselves up trying to assemble several different components into a viable transaction could mean missing that deadline. “I think they are just looking for cleaner deals,” Abeyta said. “And most of the opportunity in traditional media is getting your hands dirty.”

Sloan said there could be some opportunities in what he called “orphaned assets,” smaller parts of bigger media companies that could be combined with a SPAC to help the parent pay down debt. A SPAC, he said, would make more sense for a ViacomCBS or an AT&T than spinning off assets, because the company would get cash from a SPAC deal. But he cautioned that the driving force behind any investment is how good the business truly is.

“You can do anything, but you have to go back to the basic premise: It all comes back to the story,” Sloan said. “It can’t be the tail wagging the dog. You have to have a viable story for a viable, interesting new stock. You have to be able pass the who-gives-a-shit test.”