Ending Decrees Could Be of ‘Paramount’ Importance

The smarter way to stay on top of the multichannel video marketplace. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Since 1948, the Paramount antitrust consent decrees have determined how content can be distributed in theaters, preventing major studios from owning theater chains or engaging in “block booking,” or packaging weaker content with A-list fare (as cable operators argue happens with network deals in their space) and from granting exclusive geographic licenses.

In a move that could affect content-distribution business models across multiple platforms, the Justice Department has asked a U.S. District Court to get rid of the decrees it was responsible for imposing more than 70 years ago. Such requests are generally pretty pro forma, so look for the consent decrees to go away, though with a two-year transition period so there is time to figure out how to do it and what it will mean.

Multichannel News talked with Roman Silberfeld, partner and national trial chair at Robins Kaplan LLP and a veteran trial attorney in the content space, about what the impact could be. While he says it is too early to tell, he warns that if prices rise as the distribution channels go vertical, that could draw legal fire.

And he should know. Silberfeld has spent his life representing artists and creators, declaring proudly that he has never represented a studio. He shares his views in this edited interview.

MCN: Could you give us the “Paramount for Dummies” version of your issues?

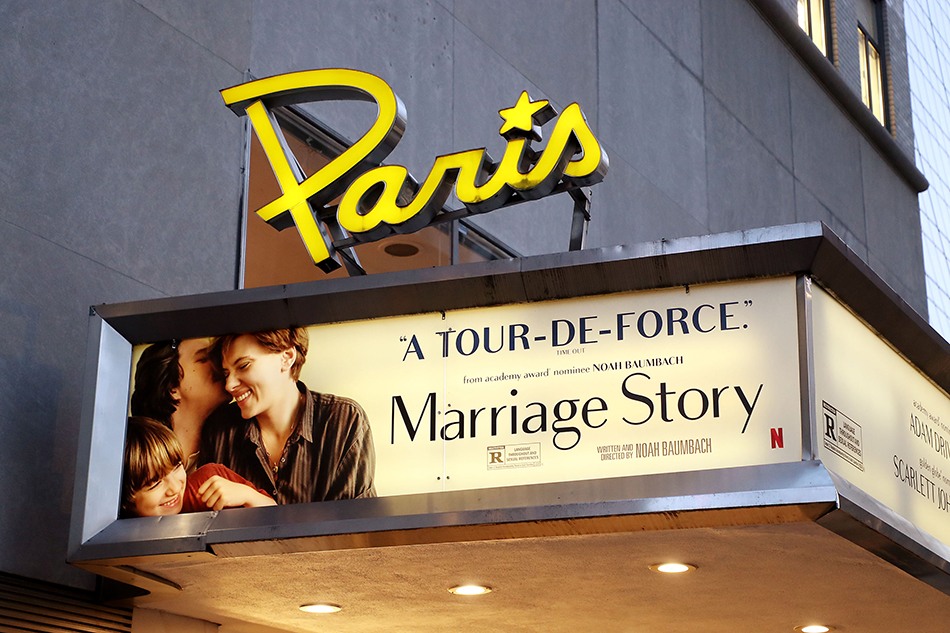

Roman Silberfeld: The “Paramount for Dummies” version of this is that where studios, and now streaming services like Netflix or Amazon, where all of these can now own the theaters — and obviously this hasn’t happened yet so we are all crystal-balling this, at least conceptually — I see a number of impacts coming down the road. And I don’t see any of them as being good.

MCN: For example?

The smarter way to stay on top of the multichannel video marketplace. Sign up below.

RS: One can go back to basic antitrust principles. Whenever there is concentration in any availability of any service or product, prices have a tendency to go up. Where the streaming services are going to be able to own theaters, the pricing for that [could rise], especially if that is bundled with a streaming service price.

Netflix may change my price to allow a Netflix theater to see something I want to see on a screen larger than I can see at home. I don’t know what the impact is going to be, but fundamentally, this was not a problem that needed solving.

MCN: Do you think all these video streaming sites can survive, or will they have to consolidate?

RS: Again, I think it is too early to tell. But there is an associated aspect to this, and that is the effect on channels of distribution of creative content that doesn’t come from one of the majors, either a major studio or one of the major streaming services.

The ability to get a really cool independent film or a documentary or a foreign film into the existing channels of distribution — that’s going to change with this rule change. The companies that are in the streaming business that are now going to possibly own theaters will change the equation about what available content means.

MCN: Talk a bit more about pricing.

RS: I don’t generally think like a studio lawyer, but let me think like a studio lawyer, or a lawyer for Netflix or Amazon. They are going to have to carefully look at their pricing methodologies now. To the extent that Netflix announces now or next year that they are going to buy 15 theater complexes in Los Angeles or Chicago or New York, and make those theaters available to their subscribers, they have to be very careful about how they price that additional feature of their service and their overall pricing.

MCN: Why?

RS: Because the threat and the risk to them will be that an attack will come.

MCN: From whom?

RS: Probably from a consumer group saying that the pricing is out of line or out of whack.

I am not sure exactly what that would look like, but there certainly has to be some sensitivity on the part of streaming services of the world if they are going to delve into this exhibition space.

When Netflix and Disney+ create content and then broadcast that content on their own streaming service, is the price of that content commercially reasonable, competitive and is that price fair to the consumer or, conversely, is the price inflated because of the dominant control which Netflix and Disney can exercise over the creation and access of its content?

MCN: DOJ antitrust chief Makan Delrahim pointed out that even with the consent decrees gone, the practices they prevented could still run afoul of traditional antitrust enforcement. Does that give you any comfort?

RS: If I had the confidence that in the grand scheme of things the Antirust Department would do something, yeah, I might be comforted. But he was announcing the fix of a non-problem. The skeptic in me says they were serving some considerable interests without studying what the effects would be.

Contributing editor John Eggerton has been an editor and/or writer on media regulation, legislation and policy for over four decades, including covering the FCC, FTC, Congress, the major media trade associations, and the federal courts. In addition to Multichannel News and Broadcasting + Cable, his work has appeared in Radio World, TV Technology, TV Fax, This Week in Consumer Electronics, Variety and the Encyclopedia Britannica.