For Netflix and Amazon, Long Road to Oscar Dominance Could Culminate Sunday

The top subscription streaming services have already spent lavishly to conquer the Emmys and Golden Globes. They’re now targeting Oscar’s biggest prize, Best Picture

The smarter way to stay on top of the streaming and OTT industry. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Coming off a pandemic year, in which most of Oscar Best Picture nominees were either produced by big streaming companies, or at least debuted on streaming services, we have perhaps arrived at the point at which Silicon Valley has not only seized economic control of film and TV from Hollywood, but the creative juice, as well.

The two, of course, go hand in hand.

The march by Netflix, Amazon, et. al. to Tinseltown awards dominance, which could culminate in the first-ever Best Picture win by a streaming company, has been more than a decade in the making and has coincided with the overall rise in prominence of the major U.S. subscription streaming services.

Famously dismissing Netflix to the New York Times 2010, Jeff Bewkes, then CEO of the erstwhile Time Warner Inc., said, “It’s a little bit like, is the Albanian army going to take over the world? I don’t think so."

On Sunday, Netflix’s Mank is up for Best Picture, Best Director (David Fincher), Best Actor (Gary Oldman) and Best Supporting Actress (Amanda Seyfried), among other Academy Awards. Netflix has another film contending for Best Picture, The Trial of the Chicago 7. That movie is also vying for Best Supporting Actor (Sacha Baron Cohen) and Best Original Screenplay (Aaron Sorkin).

Netflix is coming off a 2020 Academy Awards campaign in which it also had two Best Picture nominees (The Irishman and Marriage Story), and a breakout 2019 in which saw Roma get nominated for the top prize.

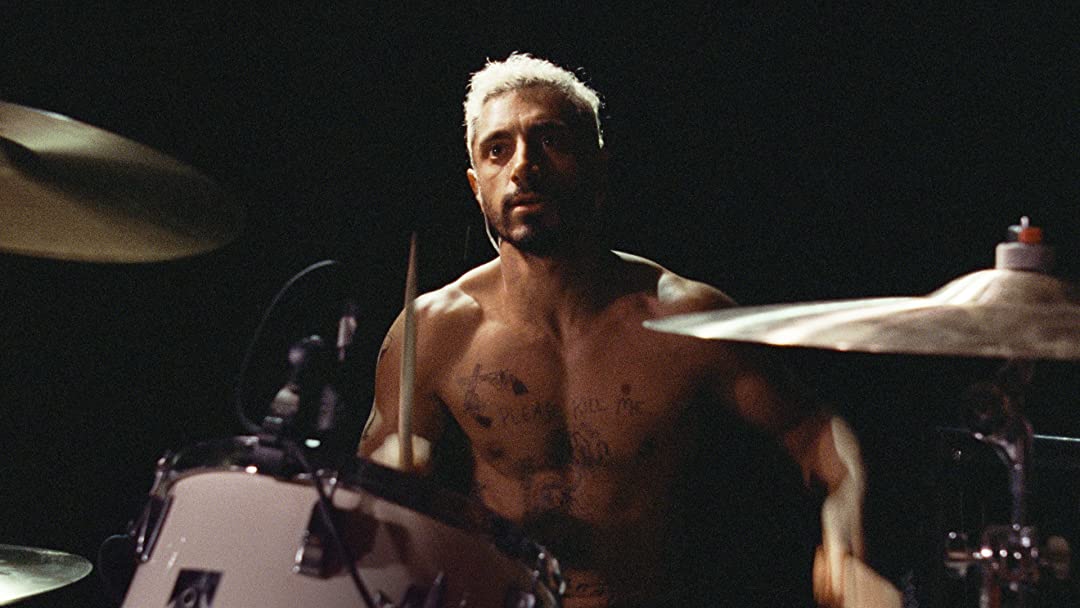

Amazon, which had its first Oscar breakout in 2017 with Casey Affleck’s Best Actor win for Manchester By the Sea, is up for Best Picture this year with Sound of Metal.

The smarter way to stay on top of the streaming and OTT industry. Sign up below.

Notably, Searchlight Picture’s Nomadland (Hulu) and Warner Bros.’ Judas and the Black Messiah (HBO Max) had their debuts on streaming services.

So in Bewkes parlance, you could say the Albanian army ended up being all it could be.

The Road to the Red Carpet

For Netflix—and for the broader streaming industry—the awards march started back in 2013, the year it debuted its first big original series, House of Cards.

That year, the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences endorsed Netflix with 14 Emmy nominations for shows including House of Cards and Arrested Development. ATAS officially opened the floodgates just as they had done in 1988 when cable networks like HBO and Showtime were first allowed to compete with the broadcast networks.

It wasn’t surprising that Netflix aggressively campaigned for an Emmy that year via costly billboards, mail promotions, parties and star-studded dinner events. The streaming service knew that if Emmy voters acknowledged the company’s original programs they would achieve legitimacy within creative talent circles. This was a necessary commercial goal in an industry that saw Netflix as a company that merely licensed old network shows, not a competitor in the originals market.

So when House of Cards garnered three Emmys, and Robin Wright took home a Golden Globe for best actress for her role in the drama, Netflix went from a deep-pocketed internet television distributor to … something creatively greater than that modest sum.

Netflix’s infiltration into the Academy Awards was more fraught.

Just weeks after garnering Emmys for House of Cards, Netflix acquired The Square, a documentary focused on the 2011 Egyptian revolution. The company self-financed a theatrical run to qualify the film for the Academy Awards, and in January 2014, The Square received an Oscar nomination for Best Documentary Feature.

Acquiring a documentary to get into Oscar’s front door was a smart move by Netflix. Financially, it’s cheap to acquire nonfiction films. And since most documentaries don’t find much success in movie theaters, the nomination wasn’t met with film-industry backlash. It was low-cost way to get itself on the major awards map.

Cut to 2019. After Netflix’s original production Roma was nominated for 10 Academy Awards, winning three– and just missing out on Best Picture—Steven Spielberg and several studio heads complained. Among the many grievances listed was that Netflix’s original films were appropriate for Emmys, not Oscars. Spielberg and the other moguls were also not happy about Netflix’s deep pockets. It was estimated that Netflix spent $50 million campaigning for Roma, while Universal only spent $5 million on promoting eventual Best Picture winner Green Book to Academy voters. In addition, Roma only spent three weeks in movie theaters.

But the Academy Award board of governors voted to keep Netflix films eligible.

“We support the theatrical experience as integral to the art of motion pictures, and this weighed heavily in our discussions,” Academy president John Bailey said in a statement. “Our rules currently require theatrical exhibition, and also allow for a broad selection of films to be submitted for Oscars consideration. We plan to further study the profound changes occurring in our industry and continue discussions with our members about these issues.”

In 2020, Netflix received 24 Oscar nominations. By that point Amazon had won three Oscars while Netflix had garnered six, but had never won in the Best Picture category.

It was also by this point that both Netflix and Amazon had developed in-house awards teams. Netflix was spending tens of millions of dollars every year on Oscar campaigns. Those dollars paid for brand equity, which led to increased subscribers and ultimately more eyes on Academy Award-nominated Netflix films. This investment also cemented Netflix as a destination for top-level creative talent.

In 2018, Netflix brought in veteran Hollywood awards strategist Lisa Taback, and Amazon hired former Variety editor Debra Birnbaum to conceive and manage awards season campaigns. That has included–pre-COVID-elaborate pop-ups and immersive experiences, nonstop screenings and Q&A sessions, expensive ads in the trades and plenty of billboards.

In April, according to Variety, Netflix’s Oscar-nominated films including Mank and documentary short A Love Song For Natasha saw a massive upticks in viewership in the first seven days following the 2021 nominations. Netflix reported that while Mank had a 702% increase in first-time viewers, A Love Song for Latasha had a 1,802% increase in first-time viewers . (First time viewers are not new subscribers.)

As Netflix’s Oscar nominations have increased each year, so has its subscriber base. At the end of 2018, the streaming service had 139 million subscribers. That number grew to 167 million in 2019, then to 203 million last year.

With 35 Oscar nods this year, including two in the best picture category, it could be Netflix’s year. With 12 nominations, including one in the best film category, Amazon could also see more golden statues.

Streaming service Oscar nomination domination isn’t a surprise. The pandemic forced movie theaters around the country to close for the majority of 2020. In April 2020, the Academy of Motion Pictures, Arts and Sciences made a one-time-only concession, permitting films scheduled to be released in theaters to still be eligible if they debuted on streaming services. Previously, movies needed to have a minimum weeklong theatrical run in order to qualify for consideration.

The question now is whether or not streaming services will once again dominate next year’s Oscars when, hopefully, the pandemic is behind us?

Netflix and Amazon have the money and plenty of prestige to attract whatever talent they want and now that COVID-19 has shifted our viewing habits and made us all streaming wizards, arguably movie theaters and therefore traditional studios will have a tough time bouncing back.

But the flip side to that arguments is that many of the films generating Oscar nods for the major SVOD services originated with traditional studios. Paramount sold The Trial of the Chicago 7 to Netflix for $56 million. Universal sold Borat 2 to Amazon for $80 million, and Sony Pictures sold Greyhound to Apple for $70 million.

“This is not a practice that we expect to see happen many times, but we’ll see a few times,” Sony Pictures CEO Tony Vinciquerra told CNBC. “We are completely dedicated to the theatrical world, but this is an opportunity that arose and we took it.”

When asked if Sony would consider releasing movies on-demand and in theaters simultaneously post COVID, Vinciquerra said, “We think that theatrical release is vitally important to the film industry and to generating the most revenue and profit. You know we just had not seen models where that kind of release schedule will benefit the profitability and the efficacy of major productions.”

With 500 titles in post-production, a slate of 71 films for 2021, over 200 million subscribers worldwide, a 2020 Q4 revenue of $6.64 billion and $17 billion to spend on original content in 2021, Netflix co-chief executive officer Ted Sarandos might disagree.