For GM: No Price Rollbacks, But Lower CPMs

The smarter way to stay on top of broadcasting and cable industry. Sign up below

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

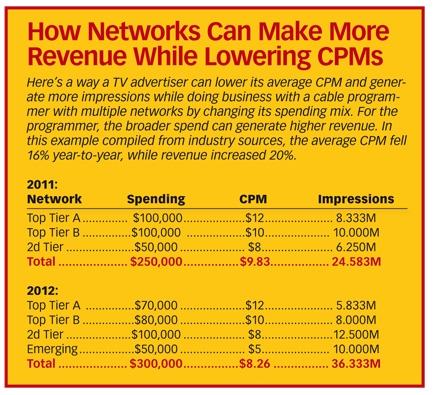

When is a rollback not a rollback? Ask the networks that

have made upfront deals with General Motors. They say creative deal-making

should put more money in their pockets without rolling back prices, as GM has

insisted. While GM won't be buying its TV spots cheap, the deals should

creatively lower the average price-per-impression by changing the mix of

broadcast and cable, networks, shows and dayparts.

The automaker hired Carat to be its new media agency last year. And word

quickly spread among media executives that Carat had assured GM that it would

be able to achieve substantial savings on its advertising expenditures.

In a series of meetings preceding the upfront, Carat and GM

gathered media vendors to explain the new rules of the road. GM had shows it owned

a piece of that it wanted the networks to run. The automaker wanted some big

marketing ideas from media vendors. And it warned that there would be winners

and losers: Media companies that didn't play "let's make a deal" wouldn't be

getting GM dollars, which have been substantial in the past.

GM showed it meant business. It pulled its ads from Facebook, just before the

social network's big IPO. It also opted out of the Super Bowl, a powerful

platform for high-profile advertisers like the major automakers.

Finally came the dreaded phone call. GM and Carat wanted networks to roll back

their primetime prices by double digits.

While it's not uncommon for new agencies to ask the networks to help them look

good when doing deals for new clients, it's usually handled with a lot more

finesse and a more cooperative attitude, network executives say. Instead, the

way GM and Carat tried to bully people rubbed networks the wrong way. "They

were like a 200-pound gorilla who thought they were an 800-pound gorilla," says

one ad sales executive.

The networks resisted. Fox reacted initially by letting GM know that unless it

dropped its demands for lower primetime prices, it wouldn't sell the automaker

spots in NFL football games, a key showplace for car ads.

The smarter way to stay on top of broadcasting and cable industry. Sign up below

The tug-of-war prolonged the upfront. Eventually, GM softened its demands and

was able to do deals with perhaps two of the big broadcasters and many major

cable players.

But ad sales execs, who declined to talk about individual clients on the

record, say there were no rollbacks in ad rates. Instead, GM and Carat accepted

the creative ways networks have to lower a buyer's average CPM, or cost per

thousand viewers. And in some cases, the nets and network groups generated more

revenue from GM. (Because it was working under a multiyear deal, MTV did not

have to negotiate its rates with GM.)

GM declined to comment on its upfront strategy.

The more options a programmer has, the easier it is to be creative. That gives

media companies with multiple networks selling at different price points a leg

up in putting together schedules that produce lower costs and better

efficiency.

On a single network, an advertiser like GM could reduce its CPMs by adjusting

its mix of programs and dayparts, such as buying fewer spots in some primetime

shows and buying more daytime and news, media executives say.

But give a savvy TV ad sales exec a few networks to play with, and the

creativity really flows. Let's say, for example, a programmer has multiple

cable networks. Some are fully distributed and are fully priced for cable. But

original programming on those networks is still significantly cheaper than

broadcast originals. That means an advertiser can lower its media costs and

continue to sponsor high-profile programming by shifting funds to cable.

Within a cable group, there are also opportunities to lower costs beyond buying

different shows and dayparts. Sometimes, steering dollars into emerging nets is

a priority. Even if a programmer gets an increased rate for its emerging network,

the client is still usually paying far less than they would on a more mature

channel. The advertiser also gets some upside if the emerging channel grows.

Of course, there are some in the you-get-what-you-pay-for school that might

question whether by seeking lower priced vehicles, GM's advertising will drive

fewer people to dealers to buy cars. Time will tell.

What's in it for the programmer? Such a deal is only worth an ad sales exec's

effort if the client agrees to spend more money-probably taking it away from a

vendor that is less creative.

Bottom line: Even a powerful advertiser has a limited amount of leverage when

it comes to buying a unique commodity like commercials. And selling TV spots

remains a very good business.

Jon has been business editor of Broadcasting+Cable since 2010. He focuses on revenue-generating activities, including advertising and distribution, as well as executive intrigue and merger and acquisition activity. Just about any story is fair game, if a dollar sign can make its way into the article. Before B+C, Jon covered the industry for TVWeek, Cable World, Electronic Media, Advertising Age and The New York Post. A native New Yorker, Jon is hiding in plain sight in the suburbs of Chicago.