How toRebuildA CableNetwork

The smarter way to stay on top of broadcasting and cable industry. Sign up below

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The cable industry has got itself

a case of rebrand fever. Numerous media

companies are already relaunching

networks, the M&A market is positioned

to heat up and a handful of

networks’ growth has plateaued.

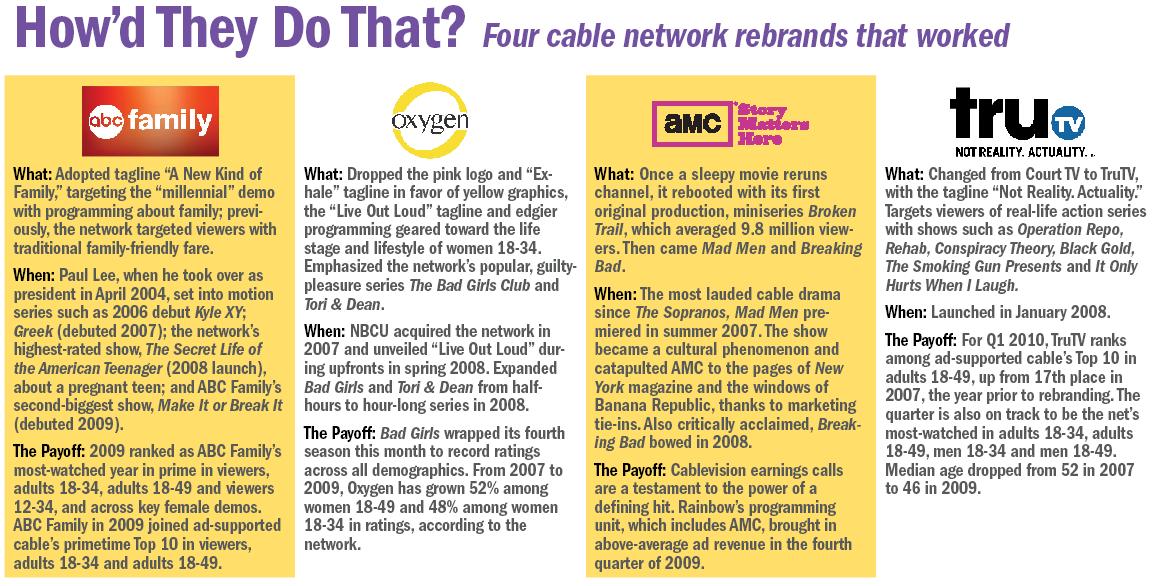

The evidence is everywhere. Discovery

is about to launch The Hub in

place of Discovery Kids, and is teeing

up its long-awaited OWN launch

on Discovery Health’s channel space.

Fox Reality is becoming Nat Geo Wild. Lifetime

is under new management and has shown signs of

needing an overhaul. MTV Networks has numerous

candidates for course correction. Scripps is

rebranding Fine Living as The Cooking Channel

while also rebooting Travel. NBC Universal is in the throes of

gussying up Oxygen. Turner is about 24 months into the new

TruTV. And Rainbow, which transformed AMC from a classic

film destination to a serious place for series, is looking to put

a new shine on Sundance and IFC.

The cable business has a long history of rebranding networks—

with dozens of hits and misses alike to show for it. Oftentimes,

it’s a new owner calling for a rebrand in an attempt to grow a new

asset. Or perhaps a network has simply hit a rut, or its owners are

looking for some fresh attention or a different focus.

And with big media companies sitting on larger piles of

cash in an improving market, more cable channel owners seem

ready to ride this wave. Executives at Discovery and News

Corp. have made it known that they’re most interested in focusing

their attention on their core businesses, so there may

be some pruning of network assets. Crown Media’s Hallmark

Channel is one name continually floated as a possible acquisition.

Hallmark is also repositioning in a lifestyle vein.

Beware the Three-Headed Customer Base

NO MATTER THE REASON, the rebranding process can

prove to be one of the most costly, complicated endeavors in

the business. Executives must strategize to satisfy the viewer,

Madison Avenue and distribution partners in the affiliate

world. And the needs of all three of these cable network “customers”

are changing at unprecedented clips: Viewers’ choices

continue to proliferate and their habits change; marketers want

more targeted, efficient buys; and multichannel video providers

face broadcasters’ push for retrans cash, leading them to

scrutinize their programming budgets like never before.

And then there’s the pressure to get it right. You get only

one shot every few years, one chance to avoid the label of the

network that cried “rebrand.”

But if you do nail it, the payoff is huge. Take NBCU’s USA

Network, now estimated to bring in $1.7 billion in revenue in

2010, according to Bernstein Research.

The smarter way to stay on top of broadcasting and cable industry. Sign up below

“USA is the best example of a rebrand,” says Lee Hunt, a

specialist consultant in the cable-branding sector. “They built

it on characters and built out a social networking site, and it’s

been number-one for years. Before, it was just a dual entertainment

channel.”

According to Hunt, the business of niche channels evolves only

to a point; viewer growth hits a ceiling because of the limited

audience, and then those niche ideas turn to a broader concept.

“Bravo was arts; it became pop culture. Turner’s CourtTV became

TruTV, and then Food Network, whose tag was about them being

way more than cooking, is now starting a cooking channel.”

On the flip side, Hunt observes general entertainment channels

moving toward a more defined niche, such as TBS’ hold on comedy

or TNT’s on drama. “Everybody wants the reach of a general

entertainment channel and the focus of a niche,” he says, arguing

further that every channel seems to be reaching for this vaunted

middle ground: general entertainment with a point of view.

Turner Entertainment Networks President Steve Koonin believes

that establishing a clear POV for a brand is crucial for

driving tune-in. “When you have a network that’s not well

branded, you’re only able to sell shows you have on the air,”

he says. His track record proves the point: Koonin’s purview

includes the top-five cable networks TNT and TBS, the nonrated

TCM, and TruTV, which in the two years since Koonin

took over has jumped from being cable’s 17th-place finisher in delivery of adults 18-49, to being ranked in the top 10 for

first quarter 2010, according to Turner research. “When you

have a brand that’s a destination, you have people who will

always come and check you out,” Koonin says.

Getting a brand right matters to marketers, too, Koonin adds:

“We’ve made this statement before and I live by it: How do

you trust your brand with networks

that don’t even have their own self

branded?”

A strong brand also presents the

opportunity to create new, non-linear

revenue. Koonin points to his

own comedy festival that sprung

from the TBS “Very Funny” brand,

as well as ESPN’s radio assets and

restaurants, as examples.

That said, there are plenty of ways to do it, as so many

success stories have proved. So, if you find yourself with a

network in some 80 million homes and marching orders to

beef up that asset, here’s what you need to do.

1. Define Your Brand

THIS FIRST STEP is the biggest in any brand relaunch, and a

delicate process at that. It’s also where the chances are highest

for fatal errors. It is the basis for all that you will do.

One of the most common mistakes in this process is thinking

it’s as simple as deciding to target a particular demographic,

say executives with the most successful branding track records.

“For millennials,” in other words, is not a brand. “If you want

to play above the rim, and you want to succeed in what is a very

successful time in top 30 cable, you need to be fi ring on all

cylinders,” says Lauren Zalaznick, president of NBC Universal

Women and Lifestyle Entertainment Networks; she oversees

Bravo Media, Oxygen Media and iVillage as well as the Green

Is Universal, Women@NBCUniversal and Healthy@NBCUniversal

initiatives. “The demo is the cost of entry.”

Rather, the architecture of a brand strategy uses the definition

of a target demo as one building block, according to Zalaznick,

who counts Bravo and Oxygen among her successes.

“My businesses have never been built on the back of a general

target demo,” she says. “There are brand strategies that are the

giant architecture into which programming strategy, marketing

strategy and sales strategy are built. It doesn’t define the brand

and does not shape the brand. In part, it’s because a demo is

exactly that. It’s a demographic, it states fact, it doesn’t state

age or income, it doesn’t state any relativity that links people

of a certain age to the essence of what they’d be coming to

you for.”

In fact, what links people to your programming—their likemindedness—

is vital to a successful brand architecture, Koonin

says; you have to define whom you want to talk to. “There

were lessons learned from the online world, that communities

are like-minded people. Television is similar, it attracts likeminded

people,” he says, adding that how a brand affects different

people leads to the demography.

The key is understanding people’s mindsets.

“We’re in a business of sales demographics,

but we’re in a business that programs to

psychographics,” Koonin says. “You have to

do both.”

And you can’t be all things to all people in

a particular age group. As Zalaznick puts it,

it’s finding out how to connect with the million viewers within

a demographic who will give you a hit, “or the several million

in a demo who will give you a monstrous hit.” Fox News is

arguably a testament to that observation.

Still, you have to start somewhere, and that’s often with

a hit show, or a network’s most successful shows. Then the

task is to research them—whom are they appealing to and

why, says Koonin, who adds that he runs Turner Entertainment

Networks with a deep emphasis on research. TNT’s dramaoriented

branding sprang from research that indicated viewers

of that network watch TV that “touches hearts and minds,”

he says. Viewers of its sister comedy-oriented network TBS

reported that they watched TV to lift their mood and used

television as a stress reducer.

Kay Koplovitz, who launched USA and what was first called

Sci Fi Channel, and now runs a media advisory practice, says

that process can take time. She offers Viacom’s Spike as an

example: “When you look at all the iterations prior to Spike,

they finally got it right. It takes time to change brands, and I

think they finally did arrive in the right place.”

When Zalaznick took over Oxygen in 2007, she zeroed in on

its popular series, Bad Girls Club and Tori & Dean. She ultimately

expanded them from a half-hour to an hour and examined how the viewers responded. Viewership exploded. During

upfronts in spring 2008, Oxygen’s new tagline and look were

revealed: Out went the pink and the “Exhale” branding; in

came the bold yellow graphics and “Live Out Loud” slogan.

She also experimented by pegging live online community

events to the shows and started to learn about the network’s

core of 18-34 female viewers. They’re looking for a little release

from their day with mindless, guilty-pleasure fun, Zalaznick

and her team discovered. Those women are living a

particularly tumultuous time in their lives, setting out on a career,

romance, family, perhaps buying a home over the course

of those 15 or so years.

Koplovitz considers Oxygen one of cable’s most recent successful

evolutions. “It’s smart, there’s more clarity, it’s a little

in your face and younger,” she says. “There’s been a step up in

recent years, just refining and adding more power to the actual

positioning statement. It’s going after [a] female audience that

appreciates tongue in cheek.”

All that said, before you get too far down any one road

on a network repaving, scour your contracts to anticipate the

programming requirements that, if violated, could backfire.

Many networks’ carriage agreements include content clauses

with such requirements. Any rebrand will be aimed at growing subscriber fees and distribution, not giving a multichannel

video provider an opportunity to call you out on a contract

infraction.

And depending on how a network was started, it may have

requirements of its own. Just ask the folks at ABC Family,

which has to air 700 Club, a throwback to its roots with founder

Pat Robertson.

2. Hire and Fire

THIS AXIOM APPLIES TO SHOWS, and sometimes to personnel

as well. Once you’ve devised your brand architecture,

you need to fi nd more shows that exemplify your brand so

you can continue building the expectation of what viewers will

find. It could be acquired programming, but you need to get

a fresh lineup on the air—quickly. If you relaunch a network

with fanfare and brand promises with one show, viewers, cable

operators and Madison Avenue will all call your bluff.

On the flip side, if something in your lineup doesn’t fit, don’t

be afraid to dump it. “If you’re going to be a brand, you have

to think some things don’t fit,” says Koonin, who canceled

his top-rated program, World Championship Wrestling’s WCW

Monday Nitro, when rebranding TNT in 2001.

Chances are you will need some new blood to get the job

done. You will need experts on the kind of programming that

illuminates your brand—and experts on marketing your brand

to your viewership and distribution and marketing clients.

Those human resources may exist in the staff you inherit, but

they also may not. Having the right strategy may be key, but

you have to do the research to make sure you have the goods

to execute it.

3. Evangelize

AS YOU FIND SUCCESS with a great brand environment,

you have to proselytize it. “If you don’t know your sales

biz, you don’t deserve to be here, but you’d be surprised how

many people don’t,” Zalaznick says. “If you really want to

play above the level of everyone else, you have to insist on

sharing proof points whether your consumer is the viewer or

ad partner. Prove it over and over and over again. We’re happy

to talk every day about it and prove every day we need to.”

Zalaznick’s points about her brands roll off the tongue like

so many versions of The Real Housewives. “My message is

always about authenticity. Be your brand,” she explains. “It’s

like people describe Bravo: It’s like being invited to the best

party you never got invited to, but now incredibly welcome at

a high-end exclusive event.”

She says this upfront season is really the second for Oxygen

on her watch, but the first with big show successes: “We still

need to do a very good job of introducing people to this new

girl in class.”

4. Stick With It

HUNT, KOONIN AND ZALAZNICK all agree that no matter

how tempting it may be to chase a hot programming

concept, it’s more important to stay consistent and on brand

for the long haul.

“I don’t think you can actually dismantle a brand in one fell

swoop, like banging an oven door,” Zalaznick says, “but you

can destabilize it if you go too far in one direction. If you keep

chasing the swinging pendulum, I’m pretty sure you will not

win overall.”

Koonin, who spent many years at Coca-Cola in worldwide

marketing, says that working for the enduring soda brand

taught him the importance of consistency. “I am fascinated

[by] and respect brand-centric networks that stay consistent

rather than try to find the

next hot thing,” he says.

“Those are the networks

that will have characteristic

success.”

“We’re going to have

ratings wins and losses,”

Koonin adds. “There will

be shows that work and

we will stumble, too, but

at the end of day, we’ll be doing the same thing tomorrow that

we did yesterday, always illuminating the brand.”

Adds Hunt, “The hardest thing to do is to stand for one

thing. It’s about trying to own a groove in someone’s brain.

TNT has done that with drama, and there are some cable networks

that are sensitive about using [the word “drama”] because

they don’t want TNT to pick up the halo.”

5. Revise, Revise, Revise

WE REALLY HAVE very incremental operating plans that

drive annual growth, and certainly we have longer-term

plans,” Zalaznick says. “But the era of the fi ve-year growth

plan is less relevant. That long-term plan today is a two-tothree-

year strategic plan with a couple of big bets for fi ve to

10 years out. The work that goes into crafting either of these

[will change] as plans change, not because we’re chasing a

pendulum but because of the daily barrage of new information

we get.”

As networks grow from being top 30 to top 20 and top 20 to

top 10, executives running the networks “absolutely need to

behave differently when we get there,” Zalaznick says. “But

the fact is we behave differently every day on our way there—

wherever that ‘there’ is.”