Is the Streaming Revolution About to Get Hit with a Major Production Work Stoppage?

The Streaming Wars have wrought worn-out legions of workers dealing with brutal production schedules, 15-hour workdays, and corner-cutting on meal breaks. And it looks like at least one union has had enough

The smarter way to stay on top of the streaming and OTT industry. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

I wrote recently about one kind of talent war unfolding in Hollywood, over big-name producer/director/writer types and the very different way Universal and Netflix approached recent deals, respectively, with Christopher Nolan (Dark Knight trilogy, Inception) and Dan Levy (Schitt’s Creek).

But there’s a different, much more traditional battle hovering at the edges of the streaming revolution, just about ready to burst forth, fueled by grueling production demands and the not-always-defined way creators are treated, both in front of and behind the camera.

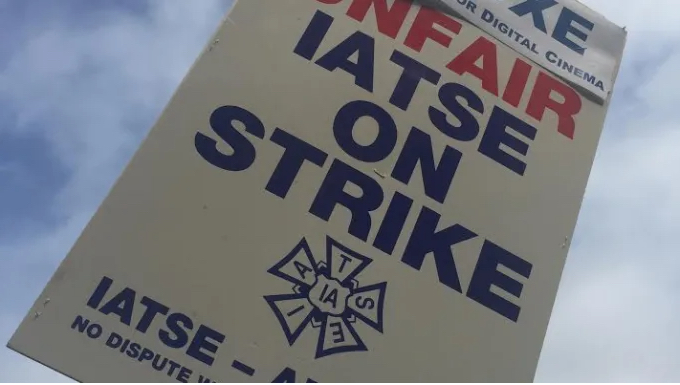

One element of this blew up this summer when Scarlett Johansson filed suit against the biggest Hollywood media company, Disney, over her compensation for Black Widow. But it’s also manifesting with one of Hollywood’s least glitzy but most fundamental unions, the International Association of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE for short).

On Monday, several of the union’s biggest locals set a strike-authorization vote for Oct. 1, allowing 60,000 members to walk out productions for the media companies that collectively make and distribute most of Hollywood’s films and TV shows. The authorization vote is considered likely to pass, but doesn’t automatically mean leadership will call a walkout.

If a strike is called, it would hit not just Los Angeles, where most of the union’s members live, but everywhere else the union’s locals operate, which is to say across the country. It wouldn’t directly influence productions in Canada, but IATSE union locals there are unlikely to continue work in the event of a strike.

“They think they got us by the balls,” Joe Martinez, a visual-effects specialist who’s part of IATSE, told Variety. “We make the product. If we don’t show up to work, what are they going to sell?”

That question is more complicated than it used to be, given the way streaming gives deep access to hundreds of thousands of movies and TV episodes without the limits of legacy distribution systems. New shows are really important, but if they’re not coming, well, there’s something else to watch.

The smarter way to stay on top of the streaming and OTT industry. Sign up below.

On top of that, some companies produce programming all over the world, well beyond the direct reach of IATSE’s U.S. contracts.

Netflix, for instance, is increasingly reliant on international productions in countries ranging from France to Mexico to India to South Korea to fill out its programming offerings. Not incidentally, as Co-CEO Reed Hastings has pointed out, some of those overseas productions have become global hits, from Lupin to Money Heist to Roma.

Netflix’s production pipeline was affected in the early days of the pandemic, when most filming across the globe halted, but since has refilled to near overflowing, Hastings said in the company’s most recent earnings call. That’s one reason why Netflix can roll out 41 features across the last four months of 2021. A strike would affect Netflix, eventually, but probably far less immediately than some competitors.

Over at Disney, CEO Bob Chapek said this week at an investor conference that his company has also been refilling its production schedule, though he warned it would remain a little bit light through Q4. Help is on the way: 61 movies and 17 series are in production for Disney Studios. Over at the TV group, 200 productions are underway with “hundreds” in development.

Chapek was trying to calm investors concerned that the pandemic’s Delta variant surge might hurt his company’s many distribution outlets. Given the importance of streaming to the company’s bottom line – both Disney Plus and Hulu are among the biggest services out there – Chapek badly needed to send those signals amid a softening stock market.

But Chapek also sent another signal that likely was not well received by Johansson, her agents, lawyers, and, as they like to say in lawsuits, others similarly situated.

“As we always have, we will compensate them fairly, per the terms of the contracts that they agreed to us with,” Chapek said. That doesn’t sound like kiss-and-make-up language to me, but then again, Johansson’s Black Widow is (spoiler alert) dead. So maybe Chapek can afford to play a little more hardball in this uncomfortably public case (Disney is trying to move it to closed arbitration).

In other cases, reports are that Disney adapting its deals to a new era for its most valuable ongoing relationships. Emma Stone got a hefty upfront payment for a sequel to May release Cruella, and Jungle Cruise-rs Dwayne Johnson and Emily Blunt weren’t left up a crappy creek without a paddle for their inevitable sequel either. Worth noting: both films had PVOD releases alongside their theatrical runs too.

At this week’s Goldman Sachs Communacopia Conference, Chapek said Disney's deals undergirding many of his company’s current films are outdated.

Most were signed years ago (Johansson’s was inked in 2017), before most of Hollywood had launched modern SVOD services, and certainly long before the pandemic made subscribing to and watching those services essential in most U.S. households.

Because those older deals no longer reflect the industry’s evolving streaming-first business structure, a “reset” is underway, Chapek said. The challenge for his business affairs attorneys is to figure out how to “bridge the gap” between the old structure and what’s becoming the streaming era approach pioneered by Netflix years ago.

That means top talent—like the Johanssons, Johnsons, Stones, and Nolans of the world—can expect much higher upfront payments, but little of the box-office bingo that characterized stars’ deals the past couple of decades.

Johansson sued because her deal was based on a share of box-office gross, a typical provision for a big star, but a bad metric when many theaters were closed and many theater goers weren’t going regardless of the film. Given the alternative to watch through the Premium VOD window on Disney Plus, those viewers spent more than $125 million, money Disney didn’t have to share with theater owners, or Johansson, a lawsuit filing revealed.

In fixing other talent deals now, Disney is “doing the right thing… because they need talent,” said Endeavor CEO Ari Emmanuel, one of the town’s most powerful agents.

That’s good. The Johansson suit is an instructive case about what’s happening at the top of the Hollywood pyramid. But down at the bottom, what’s happening with IATSE might be even more important.

After all, sure, your film would really benefit from Scarlett Johansson as its star. But even with ScarJo on the poster, does your film get made without camera operators, editors and other essential production talent who are part of the IATSE contracts? At least that’s the bet the union is making with its saber-rattling strike authorization.

The streaming revolution has, of course, sent Peak TV skyward to a whole new altitude.

In turn, for the worn-out legions of workers making all those shows, it’s meant brutal production schedules, 15-hour workdays, corner-cutting on meal breaks, and similar challenges. The union wants better accommodation for breaks and turnaround times between production hours, but is getting stonewalled by the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers, which represent the studios (and Netflix and Amazon).

It’s way too early to predict an IATSE strike. The organization has never struck before, unlike such higher-profile organizations as the Screen Actors Guild and Writers Guild.

But wearing out that behind-the-camera talent, especially amid the additional challenges of the pandemic, and pandemic production requirements, is going to matter too. Yes, we have plenty to watch on our streaming services. But this festering labor dispute might be even more important to watch over the next few months as Hollywood continues to adapt to the future.

David Bloom of Words & Deeds Media is a Santa Monica, Calif.-based writer, podcaster, and consultant focused on the transformative collision of technology, media and entertainment. Bloom is a senior contributor to numerous publications, and producer/host of the Bloom in Tech podcast. He has taught digital media at USC School of Cinematic Arts, and guest lectures regularly at numerous other universities. Bloom formerly worked for Variety, Deadline, Red Herring, and the Los Angeles Daily News, among other publications; was VP of corporate communications at MGM; and was associate dean and chief communications officer at the USC Marshall School of Business. Bloom graduated with honors from the University of Missouri School of Journalism.