Measuring the Measurers

The smarter way to stay on top of the multichannel video marketplace. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

With the number of devices and outlets where consumers can access content increasing almost every day, the business of measuring who’s watching what has evolved from a simple count of basic viewership into a near frenzy for increasingly granular information. Advertisers and networks today want not only a baseline profile of who’s watching (age, sex and demographics) but increasingly why they’re watching, where they’re watching and whether they’re paying attention to what’s on-screen.

That has given birth to a whole new subset of the typical TV-measurement business, one that is becoming increasingly important as advertisers look to target their messages and networks search for niche programming that can address the needs and wants of a specific audience. While ratings pioneers Nielsen and Comscore still dominate the measurement of broader audiences, increasingly these smaller, privately owned niche players are carving out their own piece of the measurement segment by diving deeper into audience habits and desires.

“It’s not to say that Nielsen or Comscore are bad or wrong,” TVision Insights president Luke McGuinness said. “The industry is evolving and bringing more digital-like metrics and more data-driven strategies to their TV investment. The market trends are in favor of looking at other metrics and analytics that can be used, in some cases, in parallel with the Nielsen and Comscore data set to tell a more complete story.”

The idea, then, is not to replace Nielsen or Comscore, but to enhance their ratings information with data that dives deeper and deeper into audiences.

Demos Don’t Go Far Enough

“Gender and age was great when everybody was watching TV at the same time, and if you’re doing an image or branding ad and your goal is to reach almost the entire audience,” TV [R]ev co-founder and lead analyst Alan Wolk said. “But today, people are watching at so many different times. They’re bingeing, they’re watching linear, they’re watching on different platforms and services like Tubi, they’re watching YouTube and other places were they might see your commercial. It’s important to track their viewing all across the media landscape.”

Dozens of companies have emerged to provide data that can be tweaked and massaged to paint a fuller audience picture. And today, instead of just tracking the biggest show with the biggest audience to drop ads into, ad buyers and sellers can use this increasingly granular data to track demand for a show, genre or performer; how much attention a viewer is paying to a show (and its commercials); whether the viewer is watching that show inside or outside the home (and whether it would make sense to target an ad to that specific person based on their location); and whether that ad is translating into actual sales.

The smarter way to stay on top of the multichannel video marketplace. Sign up below.

So TV is far from dead. And though the landscape has obviously changed dramatically, even the tech gurus who track viewership believe the medium has more than enough life left in it.

“If I dug a grave every time somebody said that TV was dead, I’d be in China right now,” Inscape founder and senior vice president of product Zeev Neumeier said. Inscape, a division of TV manufacturer Vizio, generates and licenses data from about 11 million smart TV sets from owners who have opted in to ad-technology companies, media buyers and networks. That data is increasingly being used by other measurement companies.

Here is a look at some of the companies carving out their own niches in the measurement game.

Assessing Demand

“It’s not just about measurement,” Parrot Analytics vice president of marketing Samuel Stadler said. “It’s about solving problems and ad opportunities.” Parrot tracks content demand from several different sources, including social media, research activities with which audiences are engaging and free streaming and downloading — what others would call piracy — to track the demand for specific content.

“We’re focused on industry workflows, we’re focused on pertinent questions of value creation, helping our studio clients, network clients, SVOD platform clients that we work with capture more value, create more value,” Stadler said.

One example: A studio or network client could use Parrot data when deciding to launch a specific channel in a particular location, whether to purchase particular programming in a market or, if it is successful in a specific market, where it should go next.

Parrot’s data set is huge. Stadler said the company tracks more than 1.5 billion daily expressions of demand in more than 100 languages and in over 100 markets.

“It is a truly global data set,” Stadler said. “What we can say about the U.S. market we can easily say about South Korea, for entire regions. We can do regional comparisons, we can do platform on platform, series on series, market on market.”

It is vastly important that the data come from multiple sources and that information be weighted based on the relative length of importance it should give each source, Stadler said, adding that more weight is given to a person actually downloading content.

“Consumption is weighted and is given far more importance than a single ‘like’ or ‘share,’ ” he said.

Assessing demand for content can be used in several different ways. In addition to assessing existing shows, Stadler said, Parrot can also track demand for long-canceled series and for shows that haven’t aired yet. “Often, we are actually brought in even pre-script and to help assess actor and [actress], meaning, ‘Can you help us predict if this show will be successful?’ ” Stadler noted. That is a harder question to answer, given all the variables that make a successful show.

“We’re not saying that data should replace these decades of user experiences that people have when they decide or make some of these decisions,” he said. “What we’re saying is let’s give data a seat at the decision-making table, which we think it really is deserving in this day and age where it is actually possible to collect billions of data points on a daily basis.”

In determining the overall ratings strength of programming, networks and advertisers are taking an increasingly harder look at where consumers are watching, whether it is at the local bar, restaurant or at a friend’s house. Nielsen has the Portable People Meter, which tracks out-of-home viewership based on a digital watermark picked up by its device when a Nielsen “family” member watches TV away from home.

Listening in to Viewing

Tunity takes a different approach. By downloading a free app on a phone, consumers can hear the audio from a set outside of the house — they are usually muted as to not disturb other patrons — by scanning a set with their device’s built-in camera. Consumers reveal some basic age, sex and demographic data to download the app, and the Tunity app takes that information and combines it with location data.

About 2.5 million people have downloaded the Tunity app, Tunity head of research and analytics Paul Lindstrom said, and from 150,000 to 250,000 consumers actively use it each month. That’s about 10,000 to 15,000 people per day.

According to Lindstrom, much of linear-TV measurement is geared toward audio. Devices pick up a code that’s embedded in the sound of a show to determine what is being watched. For digital measurement, video is the base, which he said can create a downward bias for linear TV.

An example: Two patrons are sitting at a bar, one watching NFL Thursday Night Football on their phone — through Amazon — and another watching the game via the establishment’s 60-inch TV. According to Lindstrom, the Amazon watcher is counted whether he can hear the broadcast or not, while the patron watching the game doesn’t get counted.

“There’s something wrong there, particularly when you could get to the point that Fox gets somewhere in the neighborhood of five times the unmeasured out-of-home audience in the U.S. that Amazon gets worldwide with those same games,” Lindstrom said.

A good rule of thumb is that networks should expect audience-lift levels of as much as 40% for major sports, 20% to 25% for minor sports and 15% to 25% for news programs when out-of-home is factored in, according to Lindstrom. Entertainment programs, less-significant events and awards shows are liable to be more in the 10% to 15% range, he said, with more traditional entertainment programming probably in the single digits.

While sports programming usually generates the most out-of-home viewing, there can be some surprises. For example, during the daytime, HGTV regularly has four or five of the top 10 most-watched programs outside the home each week, according to Lindstrom.

“On the surface, you wouldn’t necessarily figure that HGTV would be a big out-of-home viewing source,” he said, but its shows are family friendly; they’re not serial, meaning you can watch a show without having to have viewed prior episodes; and they’re self-contained, within a 30-to-60-minute format.

“You end up in a spot where you can watch it easily and it lends itself both to be curated and to being viewed,” he said.

Heads Up!

As the fragmentation of content distribution has led to more choices for consumers, for advertisers, it presents a problem when the target audience can be distracted by the different devices at their disposal — smartphones, tablets and laptops. In the past, just knowing that the TV was on was good enough for some advertisers. Now, they are increasingly demanding to know who is in the room watching and whether or not they are engaging with the content. Ads lose their effectiveness if no one’s paying attention.

TVision figured out a way to measure that about four years ago, developing an opt-in panel that uses facial recognition and skeleton tracking to follow who is in the room and whether they are engaging with the content on the TV screen.

“TV has a viewability problem, where often advertisers are buying these ads and they might be playing in an empty room where there’s no real opportunity for somebody to see those ads,” TVision's McGuinness said. “We’ve created this technology and this data as a means to enable advertisers to measure that and optimize for it.”

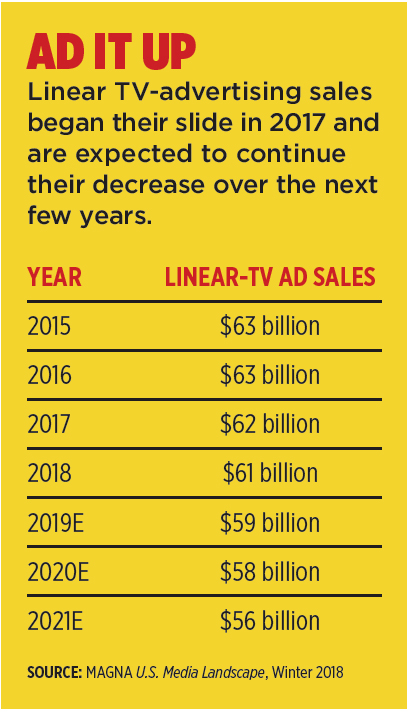

He cited a recent Interpublic Group study that said advertisers spend about $60 billion annually on TV ads. While audiences are counted when a TV set is on, 29% of the time there is no one in the room watching TV.

“That’s a ballpark [$17] billion that is being spent on ads that no one could possibly see,” McGuinness said. “The size of the opportunity to drive greater efficiency and effectiveness is huge.”

TVision data also can determine if an audience sticks around for some ads but not others, he said, information that can be used to determine the effectiveness of ads and whether an advertiser needs to tweak its creative content.

Viewers aren’t just watching their traditional networks and content on their TVs, tablets and smartphones. As younger audiences spend more time online, watching content on YouTube, Instagram and via other social-media outlets, being able to single out where those eyeballs are going isn’t the only concern. In the internet world, attaching a brand to the right online “influencer” is also growing in importance.

CreatorIQ has developed technology that tracks the content created globally by influencers — numbering more than 15 million profiles across all the major social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Pinterest, Twitch and others each day. With CreatorIQ, a client can find out which so-called influencers are more geared toward their product, and market accordingly.

“We’re able to help brands identify which influencers reach the audiences they are interested in, and what types of influencers, based on their content,” CreatorIQ senior vice president, head of sales Jonathan Kroopf said.

Brands also have to be cautious when selecting influencers, Kroopf said. He pointed to one client that engaged several food influencers to create healthy meals on a budget. That content was all tied at the end to a product designed to help people track their spending.

“What a brand will look to do is try to tie in their product organically to the influencers’ content, versus force-feeding them and having the influencer create content that is completely irrelevant to their audience,” Kroopf said.

Totally Tubular

Tubular Labs CEO Rob Gabel said tracking internet video has become an essential tool for marketers, as the internet has evolved from a digital newspaper where most of the content was text to a video-centric medium.

“The audiences have moved, especially the younger audiences,” Gabel said. “They are consuming a lot of video on social media on these platforms like live-streaming, Twitch and YouTube, as well as short-form on-demand. There’s over 1 trillion views per month on short-form, basically new media.” Those audiences are now global, to boot.

Tubular tracks social-media video, which works out to be about 6 billion snippets of content. It only tracks business-oriented video created by public figures — so no Facebook videos of the family vacation — which it then classifies by taxonomy.

Clients can use Tubular data in a couple of ways, Gabel said. Just as Nielsen ratings can determine the strength of shows with certain age and gender demographics, Tubular can show their strength globally across all media. And the data can get a lot more granular. For example, in searching for food videos, Tubular can tell which specific types of food content performs best — like vegan or health foods and salad videos versus barbecue videos. “That helps our customers craft their content campaigns,” Gabel said.

Actions Speak Loudest

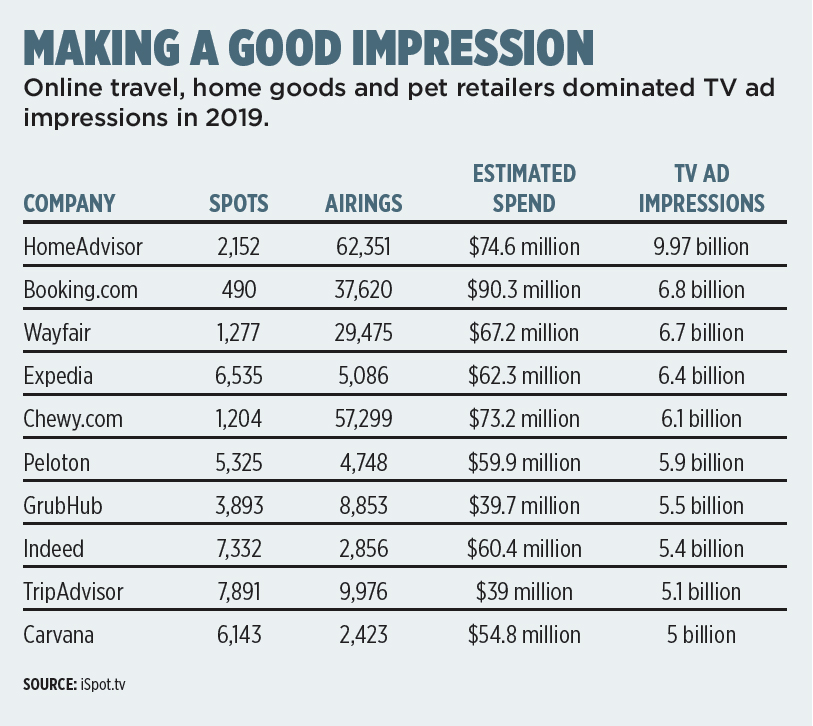

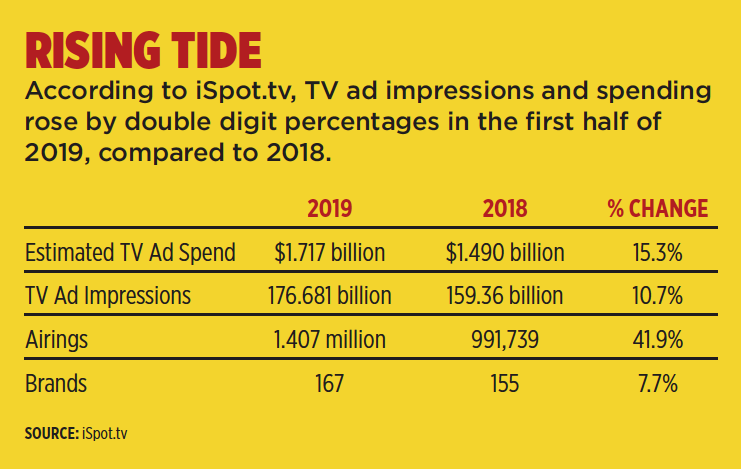

At iSpot.tv, the focus lately has been not only on tracking ad performance across platforms, but on actual consumer actions — determining how effective a TV ad spot is in driving consumers to actually buy a product.

iSpot.tv got its start in 2012 by uncoupling ads from programming in order to show how a particular ad performs and whether it was intended as part of a broader media buy or inserted into a particular individual’s TV set. “We collect [Inscape] data from the 11 million smart TVs, and then we match it up against our airing schedules and figure out if it’s a linear ad, a local market ad or if it’s addressable,” iSpot.tv CEO Sean Muller said. “But now we have to balance it up against U.S. Census [data]. That’s a very complex process, because these TVs aren’t an exact representation of the U.S. We have to correct for demographic skews that exist in the TV population both from a geographical and demographics perspective. We scale it up to the U.S.”

iSpot.tv customers include all the major networks and agencies. “We help them shift dollars from the underperforming areas to areas that are either performing or where they’re not investing and we predict they will get performance, creating a secondary layer on top of age and gender targeting that is much more focused on driving outcomes from them,” Muller said.

In essence, Muller said the iSpot.tv system allows an advertiser to determine the incremental revenue generated by in-store sales from every network, every program and all the creative they put on TV.

“They know if they spend $1 on TNT in daytime, they will get a $1.65 in return in incremental sales,” Muller said as a hypothetical example. “It gets that granular. … That’s where this industry is moving.”