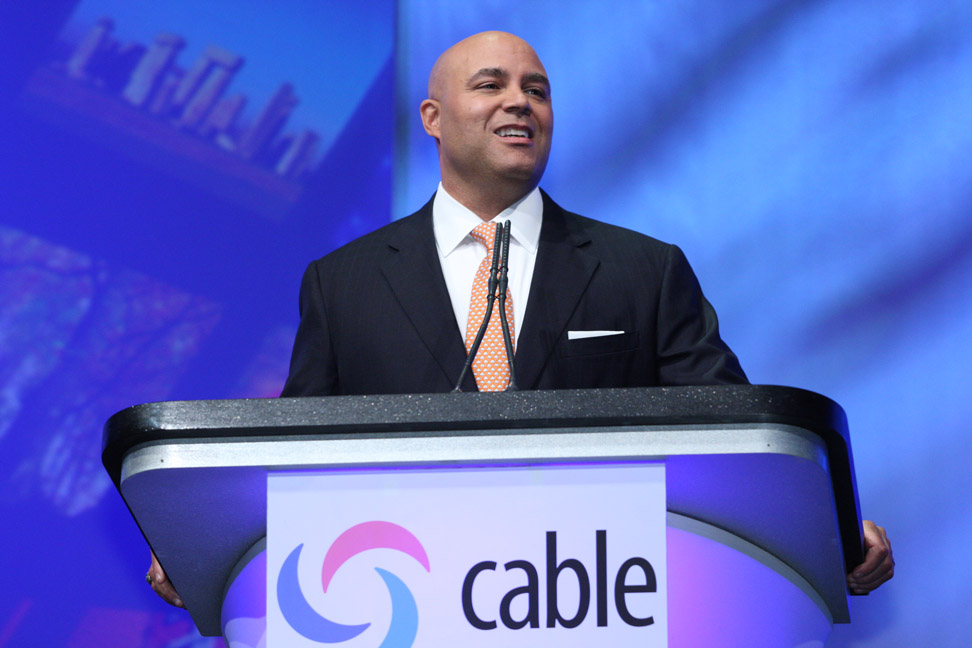

Powell: TV's Golden Age Set Against Tarnished Rules

The smarter way to stay on top of the multichannel video marketplace. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Washington -- National Cable & Telecommunications

Association president Michael Powell said Tuesday his Capitol Hill testimony

about the future of video will focus on three points: 1) that TV's golden age

is now; 2) that technology is driving choice and friction points between cable

and consumers should be removed; and 3) that the cable industry is not trying

to thwart over-the-top video.

Given those points, it's time to take a fresh look at

regulations that are premised on either a concentrated, vertically integrated

monopolist model of cable that doesn't exist or on subsidizing broadcasters and

protecting them from competition, he said during a press conference previewing his

remarks.

Whether national policy should still be predicated on those notions

"is worth some reconsidering by Congress," he said.

Powell, set to be a witness at the June 27 hearing in the

House Communications Subcommittee, said that compared to the present, TV's

so-called Golden Age of the 1950s and early 1960s was an iron age, due to the

medium's current quantity, quality and diversity of content.

He defined diversity as the type of niche programming that

would often be neglected under a traditional, ad-driven broadcast mass-audience

business model, rather than cable's dual-revenue-stream arrangement.

Do you fish, cook, dance or want to lose weight? Then

there's a cable channel for you, according to Powell.

The NCTA chief conceded that cable operators once

monopolized the multichannel video programming distributor (MVPD) market, with

98% of viewers. But he pointed out that percentage is down to 57%, and is either

flat or trending downward.

The smarter way to stay on top of the multichannel video marketplace. Sign up below.

The largest multichannel-video providers? According to

Powell, it's streaming-movie service Netflix, followed by satellite-TV

providers DirecTV and Dish Network.

On the tech front, Powell said cable is moving away from

set-tops and set-top-based navigation to cloud- and app-driven interfaces. Just

as Google can push software updates every week, the cable industry will be doing

that in the next three to five year, he said.

The federal government should reconsider a video regulatory

regime based on the "rapidly eroding predicates" that undergird it, said

Powell. The Internet is the key missing ingredient in that model, he said.

And retransmission consent and must-carry should be part of

the conversation about regulations in need of review, Powell said, although the

NCTA, with members on both sides of the fence, hasn't staked out positions on

either issue.

Like other regulations, the must-carry and

retransmission-consent rules were based on assumptions that are no longer true,

Powell said. That's despite the question of whether or not broadcasters are

charging fair value for the content, or the fact that some of that content is

of high value -- another point Powell conceded.

He said those arguments don't change the fact that consumers

are bearing those costs, part of the exponential rise in programming fees, and

thus retrans and must-carry must be part of any conversation about

affordability.

Not taking a fresh look at old regulations would also doom

stakeholders to an endless cycle of litigation, Powell suggested.

"We'll all spend the rest of our lives in court

litigating the ambiguous application of modern rules to dated services,"

he said, which would result in communications law being rewritten by judges.

Powell shot down suggestions that cable operators are trying

to stifle over-the-top competition. He noted that MSOs make really good margins

on their broadband service, and said he's never heard of a business that would

discourage high-margin business in favor of a lower-margin business, like

traditional video delivery.

"Why would that ever be rational?" he asked,

adding that at the right price, "we could sell nothing but

broadband."

Asked about usage-based pricing, Powel said cable hadn't

effectively told its side of the story. Usage-based pricing occurs in order to

fairly allocate the fixed cost of an expensive asset, and not as a means of

congestion management, he said.

As an example, Powell talked of two hypothetical houses, one

where the thermostat was kept at 70 degrees and a second where the windows were

opened to cool off. The first would pay more for electricity, he said.

He said that the FCC and even consumer advocates had

conceded that usage-based pricing would solve he called a partial solution to

network neutrality's impact on a two-sided market. If it is illegal to charge

Google or Netflix, he said, the costs are born by the consumer alone, so

usage-based pricing was a way to more fairly allocate those costs, given that

2% of users account for about 42% of traffic.

Powell, a former

Justice Department attorney, said he was not surprised that the agency was

investigating cable and over-the-top video, particularly since it was a dynamic

market with new entrants. He said that investigation was a far cry from

evidence of any antitrust violations, and that he would be surprised if it led

to any possible antitrust suit.

That's because the issues of interest to the DOJ --

broadband-usage caps, access to programming, TV Everywhere and

most-favored-nation network-carriage deals -- were looked into in 2010 during

the approval of the Comcast-NBCUniversal merger and found, at least in that

specific instance, not to run afoul of antitrust laws.

Powell also noted that during his days at the Justice

Department, such inquiries were private, not public, so someone must have a

very strong motivation to make sure everyone knew about the proceeding. He did

not point a finger at anyone, though.

Contributing editor John Eggerton has been an editor and/or writer on media regulation, legislation and policy for over four decades, including covering the FCC, FTC, Congress, the major media trade associations, and the federal courts. In addition to Multichannel News and Broadcasting + Cable, his work has appeared in Radio World, TV Technology, TV Fax, This Week in Consumer Electronics, Variety and the Encyclopedia Britannica.