Stakeholders Fight Over Need for Speed

The smarter way to stay on top of the multichannel video marketplace. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The debate over what constitutes high-speed broadband has heated up as the FCC collects comments for its next report to Congress on the state of broadband availability.

The devil is in the details, which in this case means the definitions.

At stake is whether the Federal Communications Commission gets to regulate broadband to ensure it meets Congress’s goal of universal service.

In Section 706 of the Telecommunications Act of 1996, Congress required the FCC to “encourage” the deployment of advanced telecommunications capability “on a reasonable and timely basis” to “all Americans.” The language is particularly important.

The FCC has to report annually to Congress on the state of that deployment. Under the previous Democratic FCC chair, the emphasis was on “all Americans.”

Reports under then-chairman Tom Wheeler concluded that because broadband was not available to all Americans, it was not being deployed on a reasonable and timely basis. That opens the door, at least potentially, to rate regulation or other rules meant to remove the obstacles to deployment.

RELATED: Next TV: The Speed Lowdown on Downloads

The smarter way to stay on top of the multichannel video marketplace. Sign up below.

But the FCC under its current Republican chairman, Ajit Pai, reversed that, concluding the share of Americans without access to high-speed broadband, defined as speeds of 25 Megabits per second for downloads and 3 Mpbs for uploads, had decreased. Though the decrease was less than originally thought, due to at least one carrier’s overreporting, deployment was deemed reasonable and timely according to that progress-based metric.

And while the FCC was pushed by some activist groups and others to boost the speed benchmark, the 2019 Section 706 report stuck with the current benchmark of 25 Mbps downstream and 3 Mbps upstream.

That has only fueled pushback from groups arguing that 25/3 is not fast enough; that the FCC’s deployment numbers are skewed because of bad data; and that the FCC should be looking beyond availability to how many people actually access broadband, rather than simply where they could access it. Price could also be an obstacle to broadband getting to all Americans, as well as a failure on the government’s part to sufficiently educate them on why it is so important to be connected.

Meanwhile, cable broadband operators argue that 25/3 is a sufficient benchmark, and perhaps even too high.

Here is a look at who is making which arguments, and why, as the FCC prepares to collect string on the 2020 report.

Fast Enough. Broadband providers represented by NCTA-The Internet & Television Association told the FCC it should definitely not increase the 25/3 speed threshold, and even suggested that might be too high of a metric for availability.

NCTA, which represents the larger incumbent cable operators, conceded there are still deployment gaps. It suggested, though, that the best way to fill them would be to target funds where there is no broadband at all, the so-called “unserved” rather than “underserved” population. Arguably, some available service may have to be overbuilt so that there is an ongoing business case for service that is harder or more expensive to serve. But NCTA makes it clear job one should be serving the unserved.

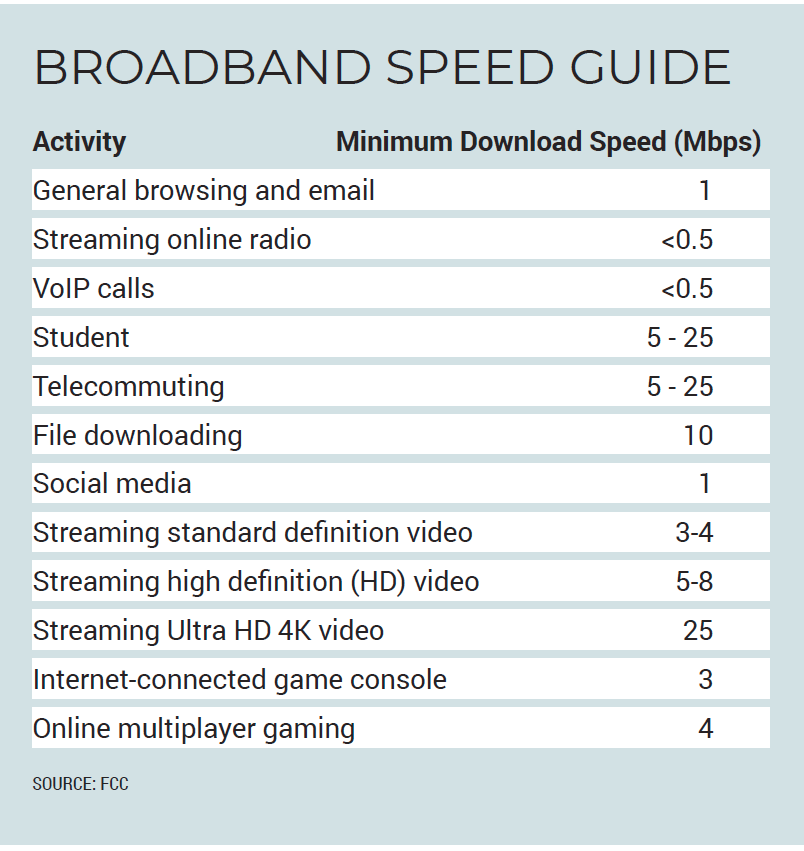

NCTA argues that the current 25/3 standard is sufficient to provide “high-quality voice, data, graphics and video telecommunications.” It also said the commission could look at speeds below that.

Need for Speed. In a joint filing, advocacy groups Public Knowledge, Next Century Cities and Common Cause, whose common cause is higher speed threshholds, told the FCC it should raise the high speed broadband definition to 100 Mbps. They argue the agency should skate to where the puck is going to be.

They concede that 100 Mbps is a “bold” approach, but say it is warranted. They interpret the mandate as requiring the FCC to “continuously improve” its speed standard, and point out it has remained the same for the past four years while innovation and consumer demand have not.

“The [FCC] proposal to maintain the current benchmark broadband speed without even inquiring what future benchmarks may be necessary runs contrary to the Commission’s congressional mandate,” the groups have argued.

Need for Blazing Speed. INCOMPAS, with members that include Amazon, Google, Microsoft [Editor's note: Microsoft says the association’s specific position on broadband "is not one we share"], Netflix and Twitter, are going the activist groups one better. Make that 10 times better.

They say the FCC’s new high speed benchmark should be speeds of 1 Gigabit per second and that it should be “future-proofing” the definition of broadband. They argue that 1 Gig isn’t an aspirational target for the future, but “rather a sensible standard” that consumers are buying now.

“The U.S. should be adopting benchmarks that reflect truly ‘advanced’ telecommunications capability, not settling for baseline speeds that major BIAS providers have surpassed in their initial offerings to consumers,” INCOMPAS told the FCC.

Been there, doing that. Certainly ISPs have made big strides in providing 1 Gbps, and talking it up as important for the future of things like AI, VR and 4K, though NCTA also says not everyone may have the need for that speed.

NCTA in January said that 80% of the nation can now receive those speeds, so even by that metric ISPs have been taking big steps. NCTA said more than 40 states have 1 Gbps offerings in both rural and urban areas, up from just 5% in 2016. “And while every consumer may not need Gigabit speeds today,” NCTA blogged, “it's imperative that networks stay ahead of innovation to enable next generation technologies and applications to emerge.”

So, by the FCC’s progress definition, a 1 Gbps speed benchmark could still pass Section 706 muster, though broadband providers clearly don’t want the FCC to hold them to that standard just yet.

Contributing editor John Eggerton has been an editor and/or writer on media regulation, legislation and policy for over four decades, including covering the FCC, FTC, Congress, the major media trade associations, and the federal courts. In addition to Multichannel News and Broadcasting + Cable, his work has appeared in Radio World, TV Technology, TV Fax, This Week in Consumer Electronics, Variety and the Encyclopedia Britannica.