The World According to Netflix

The smarter way to stay on top of broadcasting and cable industry. Sign up below

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Why This Matters: In an age when scale matters more than ever, Netflix is bulking up into TV’s most global player.

In a new world order where incumbents are running scared and new rivals are exploding business models in the TV industry, few strategies matter more than the single goal of giant media companies hoping to survive: global dominance.

Scale matters now more than ever in the television industry — for distributors and programmers — because the boundaries have been erased by new digital technologies allowing companies that didn’t exist 20 years ago to crush every competitor in sight. That paranoia over size, and a direct-to-consumer strategy, is driving every merger effort in media today, including the current tug-of-war between The Walt Disney Co. and Comcast over 21st Century Fox’s studio and cable network assets.

Netflix dominates the U.S. market. Its 57 million subscribers in Q1 was tops among pay TV and OTT providers, and it is the single largest provider of content globally, with about 68 million international subscribers at the end of the first quarter.

While Netflix’s domestic subscriber growth has been phenomenal — up 68% from its 2013 mark of 33.4 million customers — its international growth has been nothing short of spectacular, rising from 10.4 million in 2013 to 68 million in Q1.

Sanford Bernstein media analyst Todd Juenger estimated that Netflix could nearly triple its total subscriber base to 300 million by 2026.

That’s pretty good for a company that was once compared to the Albanian army.

The smarter way to stay on top of broadcasting and cable industry. Sign up below

Eight years ago, Time Warner chairman and CEO Jeff Bewkes dismissed Netflix, calling the SVOD pioneer’s looming threat “kind of like, is the Albanian Army going to take over the world?” Although Netflix may not have taken over the world yet, it is well on its way. And along that path, it is crushing traditional pay TV.

Juenger estimates there are currently about 1.1 billion pay TV homes worldwide, rising to 1.2 billion by 2026. So getting to 300 million global customers in eight years — an 11.5% compound annual growth rate, less than half the 26% pace it grew global customers in 2017 — isn’t that far-fetched. And getting to 300 million global subscribers would mean that two-thirds of all pay TV homes are not subscribing to Netflix.

“We think our base case is easily defensible,” Juenger wrote.

For the most part, Netflix in the U.S. is a complementary service, as most of its customers subscribe in conjunction with an existing pay TV platform. That’s beginning to change, too, as many pundits claim the increase in cord-shaving — reducing a pay TV package to the minimum or going broadband-only — is due largely to Netflix’s influence. And the proliferation of OTT and virtual MVPD services like Hulu, Sling TV and DirecTV Now can trace their existence back to Netflix.

Netflix’s attack on the global TV market is no accident. For Netflix co-founder, chairman and CEO Reed Hastings, it has been part and parcel of the strategy all along.

Starting with mail-order DVDs in 1997, Netflix has steadily asserted its dominance, first through accumulating digital rights to the back catalogs of pay TV networks, and later by developing its own original series.

Now, the company is focusing its sights on internationally produced programming. Netflix earlier this year said it would more than double its production spend in Europe to $1 billion, producing 100 shows in 16 countries.

Overall, Netflix is expected to spend $12.6 billion this year on non-sports content, according to UBS, up from $9 billion last year and far outpacing its industry peers.

Thinking Globally

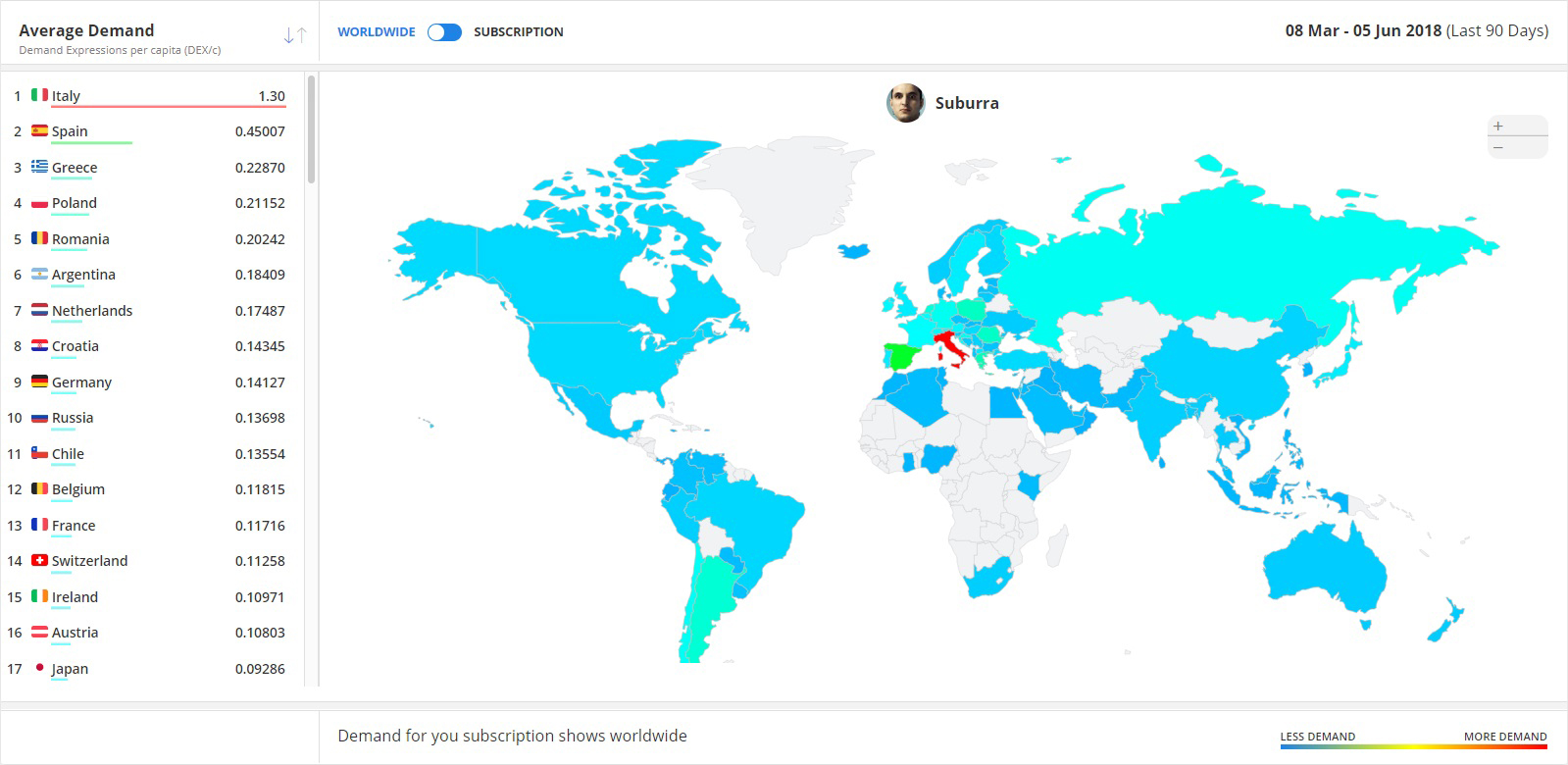

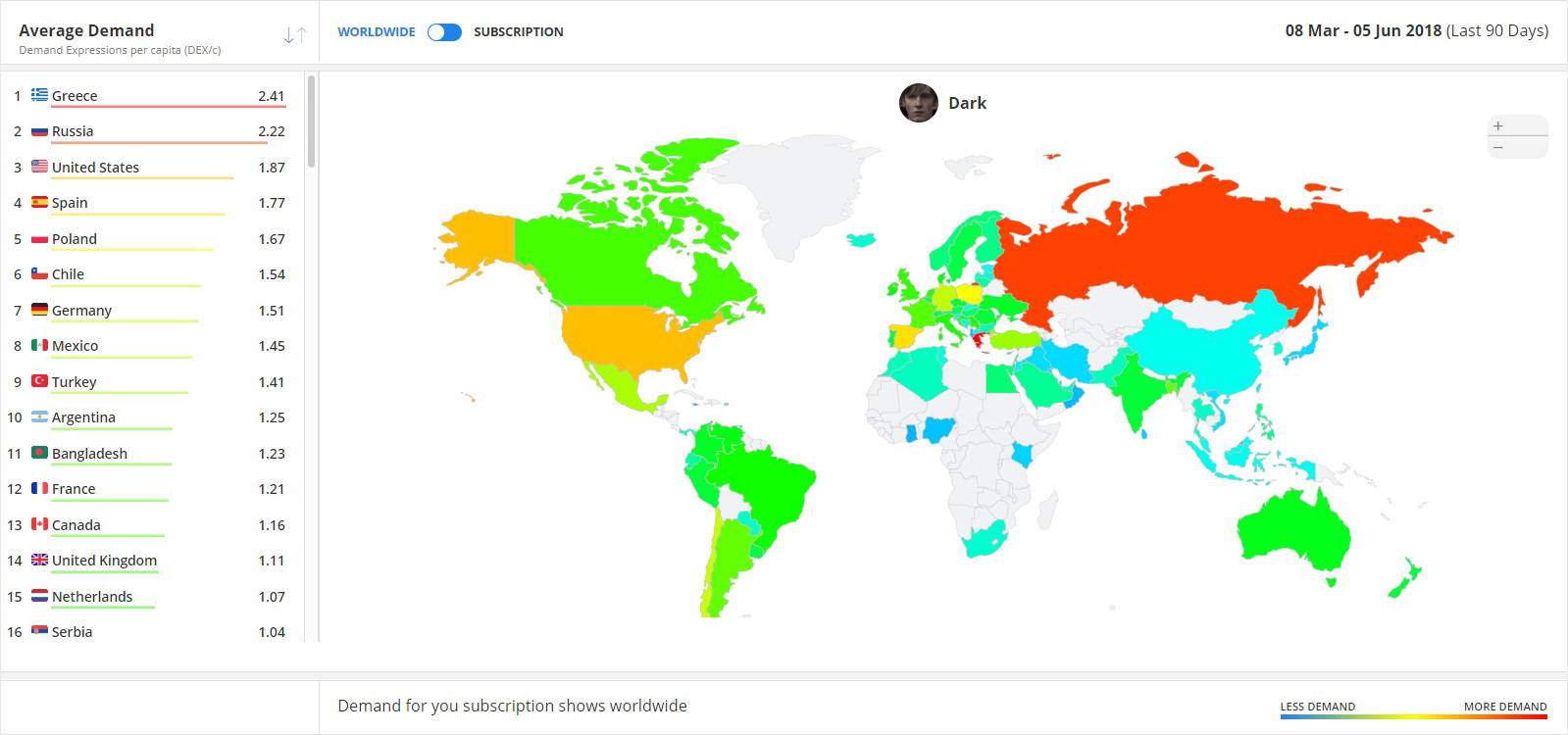

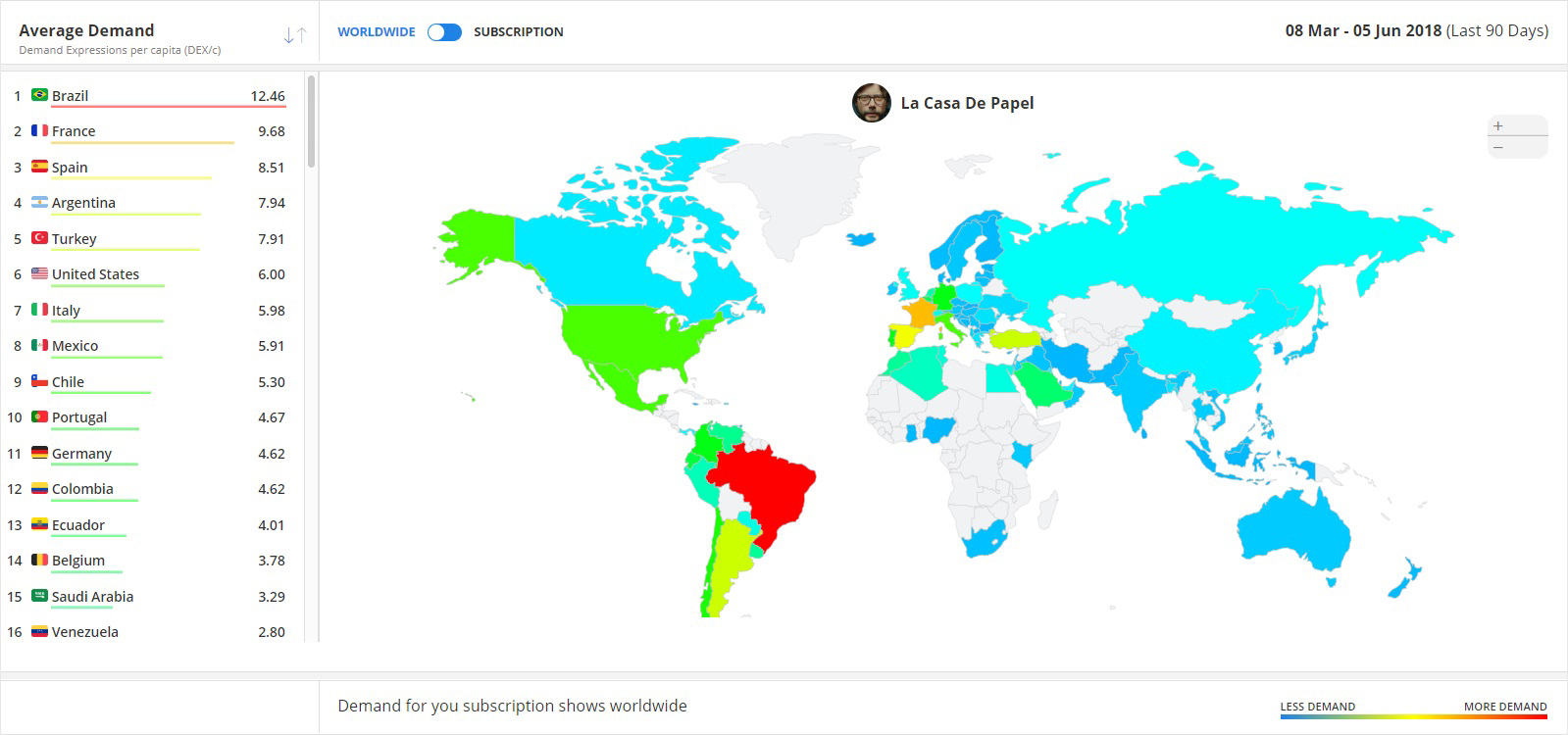

Netflix’s commitment to international programming is evident in the launch of its first German-produced series, Dark, which has been an international success, as well as with Italian organized crime thriller Suburra and Spanish thriller Money Heist.

At Parrot Analytics, which tracks global demand for content through activity on various social media, video streaming, photo sharing, blogging/microblogging, fan and critic rating platforms, as well as peer-to-peer protocols and downloading/streaming platforms, the trend is not a surprise. But Courtney Williams, Parrot’s European regional director, said the rise in popularity of Netflix shows produced outside the U.S. can be traced to one factor — its ability to spend and spend big.

“What Netflix has changed is that it has started to spend a lot more money on things like Dark than your average German player would be able to, and it has created an immediacy, a sort of instantaneous access to the content, at the same time all around the world,” Williams said in an interview. “Your big U.S. shows, even Game of Thrones, where HBO has got pretty aggressive global distribution, would not have the same kind of immediacy and immediate relevance as Netflix can provide.”

For some analysts, the global popularity of Dark — Netflix said 90% of the viewing of the German-language drama came from outside of Germany — totally turns the return on investment (ROI) model on its ear. In the past, the general consensus was that foreign language productions were only popular in the countries where that language was spoken. Now, with Dark, Money Heist and Suburra, Netflix is proving that foreign-produced content can generate returns worldwide.

U.S.-produced content still travels well, though. According to Parrot Analytics, U.S. shows such as Stranger Things, Orange is the New Black and Marvel’s Jessica Jones dominated the top 10 most in-demand digital original shows outside the U.S. in the first quarter. But foreign-produced fare is increasingly cracking some surprising markets. Narcos, for instance, ranked No. 15 in the U.S. in Parrot’s Q1 in-demand digital rankings, but was No. 3 in Italy, No. 4 in Greece and No. 5 in Belgium. Dark finished in 18th place in the U.S. in-demand ranking, but placed third in Greece and seventh in Switzerland.

Back in the States, Netflix has continued to flood the market with original programming. At last month’s MoffettNathanson Media & Communications conference, Netflix chief content officer Ted Sarandos said 85% of the SVOD pioneer’s content spending is on originals. He predicted that Netflix would have about 1,000 original movies and series by the end of 2018, 470 of which would be launched in the second half of the year.

While Netflix continues to ramp up spending — Juenger estimated it could increase its content budget to $20 billion by 2026 — it is valued in a vastly different way than the rest of the media business. This year alone, Netflix anticipates a cash burn of between $3 billion and $4 billion. And the company has amassed a huge debt of about $8.5 billion, including its April bond issuance of about $1.9 billion, and has about $4.5 billion in cash and cash equivalents.

So far, that hasn’t been a problem. Debt markets are happy to lend to Netflix as long as the subscriber increases continue. But should that falter, the company could find it difficult to fund future growth. “Despite the strong equity performance, management continues to debt-finance the cash burn in a rising rate environment,” Morgan Stanley debt strategists David Hamburger and Lindsay Tyler wrote in a note to clients. “While we like the growth trajectory, unless the cash burn and funding dynamics change, we think Netflix’s debt balance will continue to grow, moderating the original appeal of the company’s scarcity value.” So far, the market is ignoring the debt, content to focus on subscriber growth, and it’s rewarding Netflix investors handsomely. In June, Netflix not-so-quietly surpassed Disney as the largest media company in the world in terms of market capitalization.

Netflix ended June 6 with a market cap of $159.01 billion, compared to $148.59 billion for Disney. And Netflix stock, once a roller-coaster ride for investors, has been the pillar of stability this year, rising more than 90% since the beginning of 2018 to $367.45 per share on June 6. Disney, by comparison, has fallen about 5% since the beginning of the year, while Comcast has dipped 20% in the same time frame.

The cable industry has been kicking itself for years for missing the Netflix boat. Many analysts credit Liberty Media chairman and cable legend John Malone with coming up with the concept decades ago, only to be quashed by cable companies more interested in protecting their installed base.

Programmers weren’t free of blame, either.

“The content companies never took Netflix seriously,” Pivotal Research Group CEO and senior media & communications analyst Jeff Wlodarczak said. “They all thought that selling digital rights to Netflix was all incremental revenue, not thinking that Netflix could lever that content into developing an audience and then moving to original content and massively reducing their reliance on those media companies.”

Later, the concept of TV Everywhere, or full on-demand availability of a content provider’s library via pay TV, was stilted because programmers didn’t want to give access to their shows without an additional charge and distributors chafed at having to pay twice for content they felt was already too expensive.

While that battle raged, Netflix happily paid the going rate for content and built its service.

“The genius of Reed [Hastings] is how he levered the hubris and frankly, the arrogance of the media companies and net neutrality laws to build what is arguably the most powerful media/distribution company in world,” Wlodarczak said.

Meanwhile, domestic video consumption is slowing all over in the U.S. Cable subscribers have been on the decline for more than a decade, and broadband, the pipe that carries services like Netflix to the masses, is seeing its growth wane. Comcast, which has 25 million broadband customers across its footprint, has seen growth in that segment dip steadily over the past two years, slowing from 1.37 million additions in 2015 to 1.17 million additions in 2017.

Operators have insisted that although the broadband market is maturing, they still see growth opportunities in domestic video and broadband services. But their actions speak differently.

Comcast’s play for Sky, the U.K-based satellite operator with 23 million subscribers across Europe and 39% owned by Fox, is largely seen as proof that the future is outside of the U.S., despite the cable operator’s protestations.

“[W]e love our core businesses,” Roberts said on Comcast’s Q1 earnings conference call the same day as the Sky announcement. “And anybody who is viewing this as some divergence from that is not reading us properly, in my judgment.”

Finding Growth, Scale Overseas

But the Sky deal, and a possible bid for the Fox assets pledged to Disney, would boost international from 9% of total revenue to 25%. For some people in the cable financial community, Comcast’s play for Sky can only mean one thing — it doesn’t think it can squeeze any more growth out of the U.S. business.

“It’s very hard to make peace with this,” said one member of the investment community that asked not to be named.

On the same conference call, Roberts said that Comcast didn’t have to do the Sky deal — just like it didn’t have to purchase NBCUniversal in 2009, and look how that worked out — but it saw an opportunity.

“I don’t think international broadly is a strategy,” Roberts said. “I think it is a unique asset in Sky’s case that fits well within the mix of businesses we have already got, and is aligned with our existing strategy of integrating content distribution.”

But again, the stars seem to be aligning differently.