The smarter way to stay on top of the streaming and OTT industry. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The key to controlling the television industry in the years ahead rests with the interface, as the companies that control that platform will control access to programming.

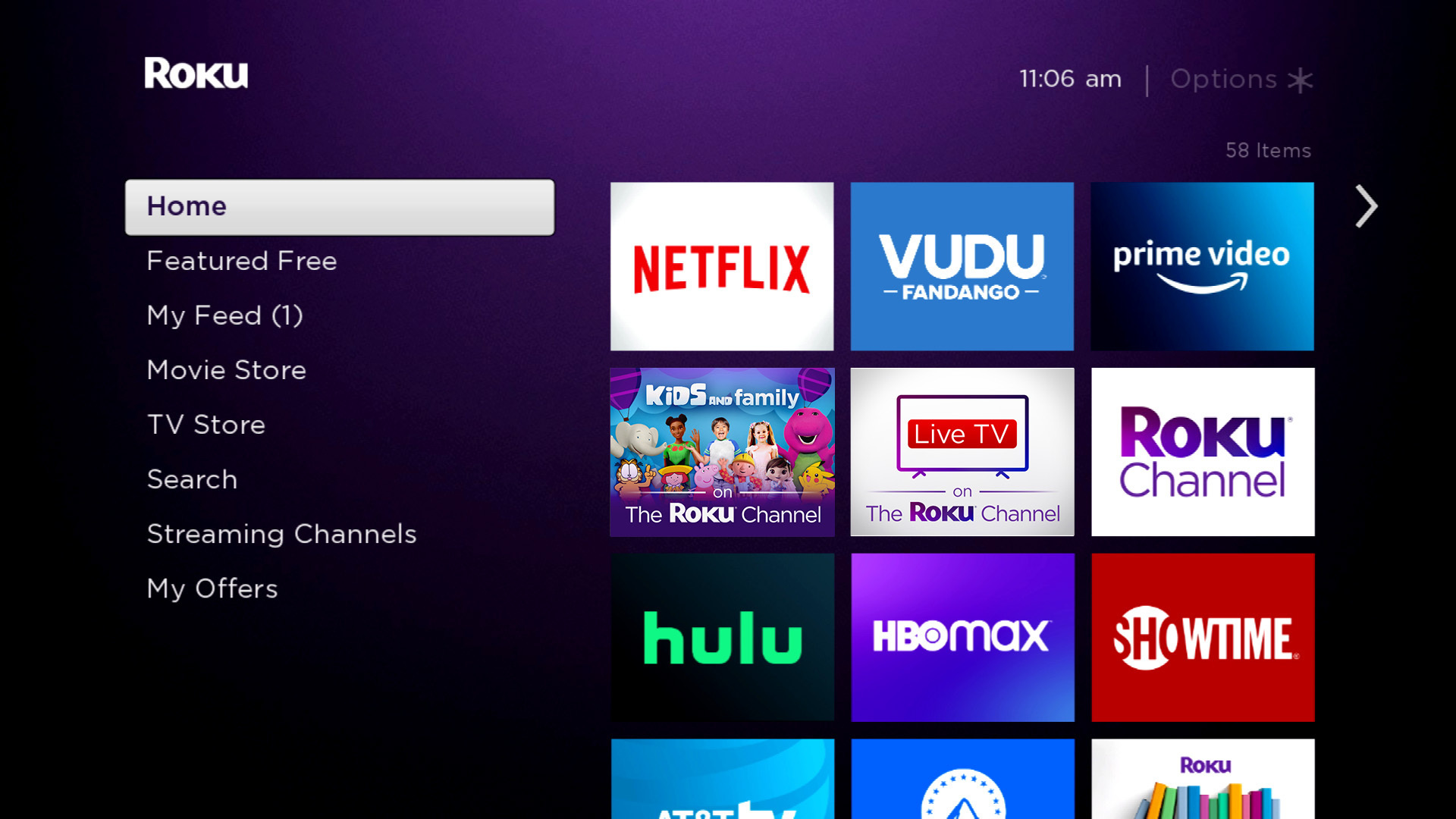

At present, the interface in the U.S. is mostly controlled by smart TV OEMs and peripheral device manufacturers like Roku and Amazon, which also license those interfaces to various TV manufacturers.

So how did we get here, and what does it mean?

In the old world, MVPDs controlled the interface, or what passed for an interface anyway—an old school program guide.

It wasn’t the interface that mattered but rather the programming that made it onto it. The MVPDs cut carriage and retrans deals with various cable and broadcast networks, and thus for a new network, getting a deal with a major MVPD like Comcast or DirecTV was a huge win.

Fast forward to 2021 and that same gatekeeper role is being played by the companies who control the interface.

There’s no official carriage fee transaction, but the more interfaces a streaming service appears on, the greater the chances it will attract a larger audience.

The smarter way to stay on top of the streaming and OTT industry. Sign up below.

The importance of this was revealed last year when both HBO Max and Peacock failed to strike deals with Roku and Amazon at launch and their early subscriber numbers were negatively impacted.

In the earlier days of streaming, it was the app creators who had the upper hand, not the device manufacturers. A streaming device or smart TV that did not provide access to Netflix was pretty much dead on arrival.

That’s probably still the case with the Netflix app. But now there are a plethora of other apps, both free and subscription, and the device manufacturers have realized that they’re not in much danger of losing customers if they don’t have a specific new app.

In the long term, this will not be much of an issue for the Flixes, the nine multibillion dollar streaming services, as they will eventually get slots on just about every device manufacturer’s interface due to demand for their product.

Rather, it is the smaller services, both free and subscription, which will be the ones who will need to curry favor with the manufacturers, as there will be little demand for them from consumers.

This then leads to the second reason why the interface matters so much: recommendations and discovery.

With so many services and so many shows available, recommendations and discovery via the interface will assume a greater role.

This represents a critical secondary revenue stream for the manufacturers too, as they are going to charge the various apps to run promotions for their shows and to feature them on their home screens, program guides and “available channels” menus.

In writing our recent special report on the Emerging Smart TV Ecosystem, one key theme from both programmers and distributors was that the home screen of a smart TV or streaming device was the ideal location to run promotional ads for new series and streaming services. Many compared it to point of purchase display ads in supermarkets. As in “the viewer is there, they’re looking for something to watch, they’re never going to be in a better position to click on your ad and watch a preview.”

The current U.S. market is pretty close to peak right now. Between them, Roku, Amazon, and the three big TV OEMs—Vizio, Samsung and LG—control around 75% of the market.

If you figure that Apple controls another 5% of the remaining share, that doesn’t leave a whole lot of room for the next round of entrants. And there is a next round of entrants coming into the market now, including large and well-funded players like Google, Comcast and Walmart.

That puts the newcomers at a disadvantage just on market share alone—it’s going to be hard for them to build up any kind of a base, at least not for the first couple of years.

This then creates an additional problem: If I'm rolling out updates of my app, my first priority will be those interfaces with tens of millions of viewers, not the ones with a few hundred thousand, which only serves to put the newcomers even further behind the eight ball.

That said, the U.S. market is not likely to be the place where these interface battles take place.

As per Evan Shapiro, whose media maps have become legendary, 42% of the global market is pretty much up for grabs. That’s an interesting stat because not all the major players in the U.S. market are global in scale.

Take Roku, for instance, which is just starting to roll out in Europe. Roku doesn’t have anywhere near the prominence in Europe that it does at home, let alone in the developing world.

This is where companies like Amazon and Google, with their global presence have a shot to greatly expand their footprint, ditto global OEMs like LG and Samsung.

Their victory is far from guaranteed though. Roku could license its operating system to TV manufacturers overseas the way it does in the U.S. market. There are also players like Sony and Microsoft who have global presence and could make an interface push. And that’s just the known players.

Chinese internet giants like Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent are also likely to try and grab a piece of the TV interface pie, especially in developing markets. There are also independent companies which white label their interfaces, and which might become an attractive option for companies concerned about the data and privacy issues inherent in working with companies like Google and Amazon.

This will all play out over the next five to 10 years as streaming takes off globally and the shrinking cost of TV sets means that more and more households will acquire a new smart TV. And when they do, the quality and ease of use of that smart TV’s interface will be of primary importance to them in making their purchase decision.

Stay tuned.

Alan Wolk is the co-founder and lead analyst for media consultancy TV[R]EV